Identifying Good Practices of Use: Insights on the Consumption of Sustainable Fashion in Uruguay

Authors: Micaela Cazot and Lía Fernández, Montevideo, Uruguay. Bachelor’s degree in Industrial Design (Textile/Clothing Profile)

Original title: Identificando buenas prácticas de uso: reflexiones sobre el consumo de la moda sustentable en Uruguay.

Aim of the study/exercise: Educational, as the Final Degree Project for a Bachelor ‘s degree in Industrial Design – Textile/Clothing Profile, Universidad de la República (Montevideo, Uruguay).

What was the objective of the study?

To understand and analyze the clothing usage practices of a group of Uruguayan women who consider themselves sustainable in their way of dressing. The focus is on the users’ characteristics, circumstances, and life situations, seeking to identify good consumption practices based on the connection formed between individuals and their garments, as well as between garment and garment.

Context: Influence or inspiration

The choice of this topic arises from the motivation to visualize the role that design plays in generating good consumption practices. It is valuable to analyze the connection between consumers and their garments to recognize various factors in the purchase and use of clothing, aiming to raise awareness and contribute to the future of fashion by promoting more sustainable consumption.

How was the method used?

This method consists of two parts:

- an interview, with questions aiming to understand the participant’s relationship with sustainability and practices of acquisition, use and disposal of clothing.

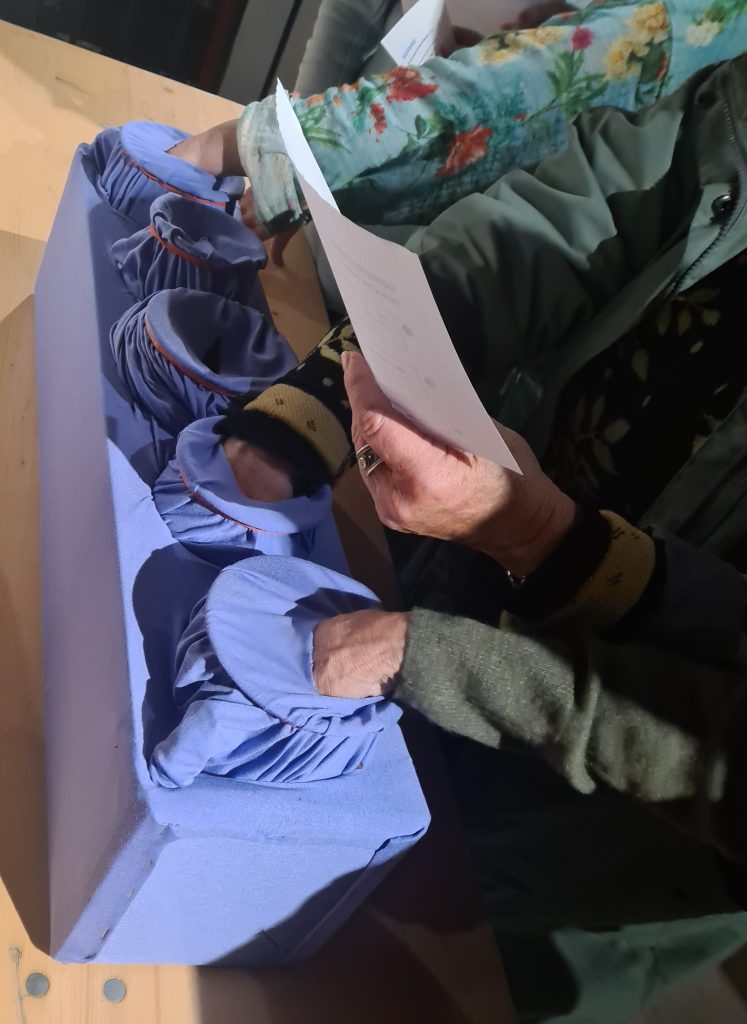

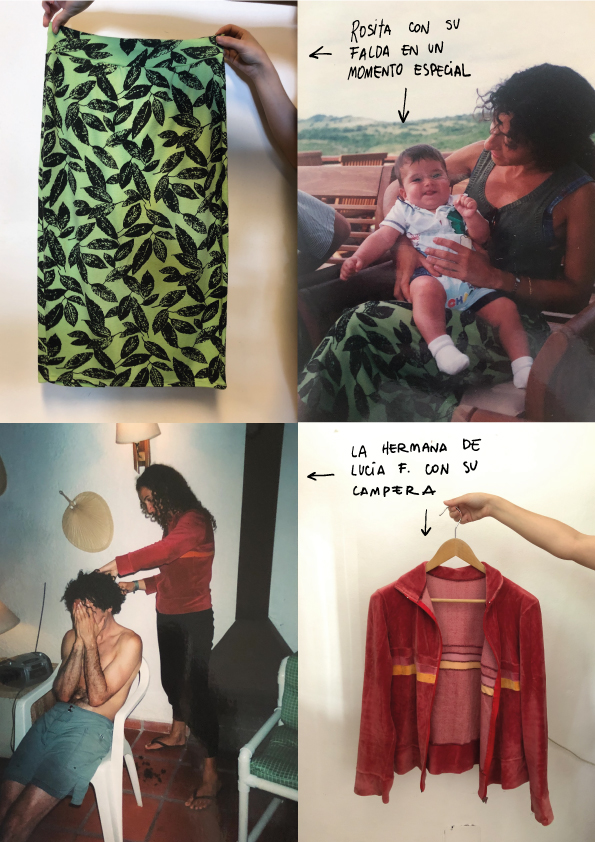

- a wardrobe visit, where they are asked to select an item of clothing for each of the following categories: the newest, the oldest, the most used, and the least used. We then proceed to take pictures of the items and ask questions related to each of these categories.

To carry out this method a characterization of the Uruguayan sustainable fashion consumer is made to search for participants, who ideally have different ways in which they experience sustainability. This search resulted in a selection of five women from five different generations residing in Montevideo which includes: leaders of sustainable fashion in Uruguay, design professors, a person from our close circle and a person involved in the second hand business.

After the method is carried out, the information is evaluated and reviewed by comparing the answer for each question and the garments in each category, looking for similarities and differences.

What happened after the study/exercise? What about the results and objectives?

As this study was produced for a final degree project, it was recorded thoroughly in a document that can be found in the institutional repository of the University.

How could this specific method be used by others? What are other insights/results that this method can generate?

As this method was only introduced to a small number of people in Montevideo, we believe it could be adapted to be used in other parts of Uruguay or in other parts of the world, and even with more people involved. Depending on the region where this method is applied, it will yield conclusions that reflect the culture and society that inhabits that place, from a sustainable point of view.

We believe that what matters the most is that, as designers, we must recognize the importance of understanding the complexities of clothing and feelings by addressing them in our creative work. Creating awareness about the emotional bonds and individual circumstances that influence consumption habits, and how these can be channels for fostering more sustainable practices in fashion.

What insights does this method generate?

Regarding the data provided by both parts, we can observe certain recurring patterns across interviews. For instance, all the garments we visualized with the users in their homes have stories beyond their materiality; they are not mere pieces of clothing but rather reflect nuanced aspects of the person who wears them and their emotional attachment with each item. Furthermore, we found that all of the participants have a relationship with sustainability that goes beyond responsible consumption of clothing and also encompasses other areas of their life such as their profession, their hobbies, their eating habits and their life experiences. All of them admit that they do not consume clothing in large quantities and no more than ten items of clothing a year enter their wardrobes. This indicates a strong inclination to consume less when one has a sustainable philosophy.

The habit of holding onto clothes that they do not wear for a long time is very present in these participants, because they believe that there is the possibility of using them again later on. They see the future potential of their clothing, rather than discarding it by not wearing it for a while. This generates an emotional connection with the garment, since it is seen as an opportunity instead of waste.

On the other hand, users who engaged in second-hand consumption expressed that accessing this market requires time and accessibility that not everyone possesses. There is a process behind the choice of second-hand garments, which sometimes becomes a matter of privilege. Similarly, garment repair as a tool to extend the lifespan of clothing is not available to all consumers due to lack of knowledge.

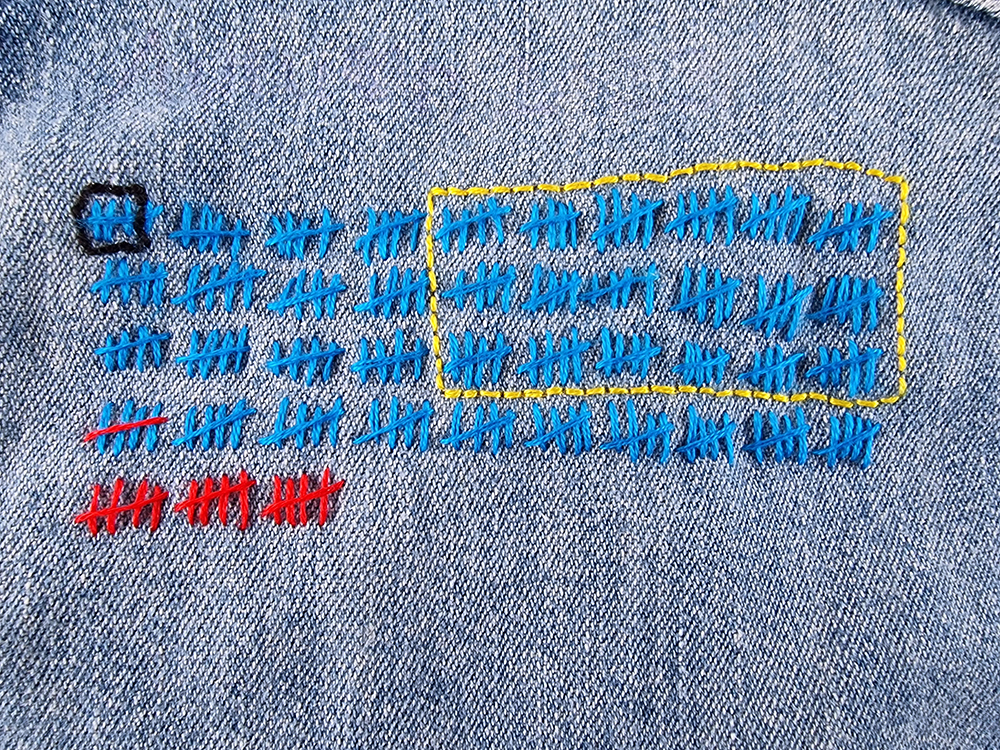

Conversely, some participants opt to make adjustments to their garments through modifications, repairs, or redesigns. Others enhance their wardrobe creativity by borrowing clothes from friends and family, finding enjoyment in mixing their own clothing with others’, thereby strengthening their individual fashion perception by exploring new dressing styles.

This more conscious approach to dressing reflects a trend towards sustainable fashion and a deeper connection with personal expression through clothing. Consequently, these users discard clothing less frequently.

In summary, the diversity in the responses obtained highlights the complexity and richness of the experiences, providing a profound and contextualized insight.

References:

- Armstrong, C., Lang, C. (2018) “The Clothing Style Confidence Mindset in a Circular Economy” Aalto University, DOI: 10.1002/cb.1739.

- Bjerck, M., Klepp, I. (2014) “A methodological approach to the materiality of clothing: Wardrobe studies”, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 17:4, 373-386, DOI: 10.1080/13645579.2012.737148.

- De León, L., Haugrønning, V., Maldini, I. (2023) “Studying clothing consumption volumes through wardrobe studies: a methodological reflection” The 5th Product Lifetimes and the Environment (PLATE) Conference, Espoo: Aalto University, pp. 610-616.

- Fletcher, K., Klepp, G. (2017) “Opening up the Wardrobe: a methods book”. Novus Press, Oslo: Noruega.