This is a letter sent to commissioners and members of the European Commission in October 2022, from 4 participants in the Wasted Textiles project that explains their suggestions for a way of developing an EPR scheme that addresses volumes. They suggest an Eco-modulation based on volumes in the waste and therefore include the growing online trade.

How to make sure Extended Producer Responsibility becomes a silver bullet

We would firstly like to recognize the immense effort made by the EU Commission in launching the EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles in the spring of 2022 and welcome the long-awaited focus on this sector. We would also like to express our appreciation of the strategy’s systemic approach to tackling the various challenges in the textile sector. We especially welcome that the strategy addresses fast fashion, the problem of synthetics and the need for EPR.

We are an applied research consortium under the umbrella of the project Wasted Textiles, which represents strong expertise on textiles, i.e., consumption and wardrobe studies (use, reuse, laundry, repair, disposal), end-of-life practices and waste analysis, fibres and measurement tools, greenwashing, marketing claims and consumer communication and, business models. We wish to offer our interdisciplinary expertise and in-depth knowledge of consumer research, waste and recycling management and policies from 30 years of research and recycling industry development. Wasted Textiles is led by Consumption Research Norway (SIFO), a non-profit, transdisciplinary research institute at the Oslo Metropolitan University. SIFO has a history going back to the 1930s and the birth of home economics and has worked with clothing consumption from the start. Today the institute has extensive research on clothing, especially the use phase.

With this letter, we would like to express our support for the EU Commission’s work within textiles and at the same time highlight key areas of concern that need to be addressed for a much-needed systemic change within the industry. Specifically, this letter concerns the development of harmonised EU Extended producer responsibility (EPR) rules for textiles with eco-modulation fees as part of the forthcoming revision of the Waste Framework Directive in 2023.

Norway was one of the first countries in Europe to implement Extended Producer Responsibility for packaging waste and electric electronic equipment (EE goods) and batteries during the early 1990s. The law from 2017 replaced the voluntary industry agreements from 1994. The National Waste Association of Norway (Avfall Norge, part of the Wasted Textiles consortium) has a history dating back to 1986. Norway also got its first Pollution Act in 1981.

We believe that harmonised EU EPR rules for textiles can be an important instrument to bring the needed systemic changes in the textile sector. In line with a recent report by Eunomia “Driving a Circular Economy for Textiles through EPR”, we believe the aim of the EPR scheme must be the reduction of environmental impacts from the textile sector. This is in line with the original definition of EPR from the Swedish researcher Thomas Lindhqvist from 1992:

“Extended producer responsibility is an environmental protection strategy to achieve an environmental goal of reduced total environmental impact from a product, by making the manufacturer of the product responsible for the entire life cycle of the product and especially for the return, recycling and final disposal of the product. The extended producer responsibility is implemented through administrative, financial and informative instruments. The composition of these instruments determines the exact form of the extended producer responsibility.”

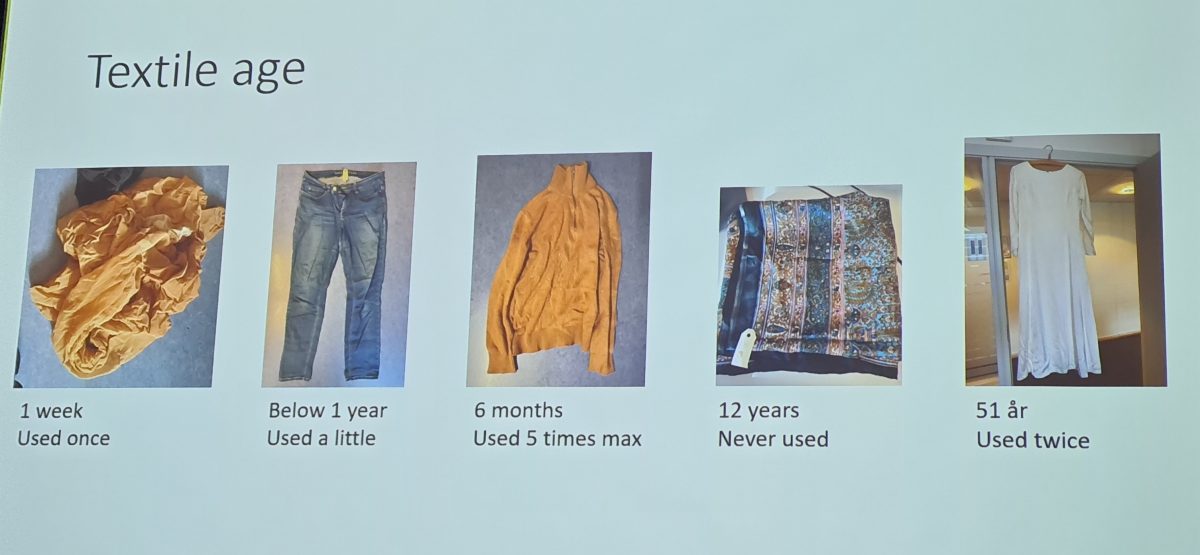

Our point of departure is that the biggest challenge in the textile sector is overproduction. The amount of clothes produced and sold has increased drastically in the past 20 years. This means that each individual garment is used less and less. In order to reduce environmental burdens, measures are therefore needed that not only address the product’s design but above all the quantity of products. It is those who produce the clothes that are used the least – or never even used at all – who emit the most. At the same time, it is the clothes that are worn the longest that burden the environment and waste systems the least. In other words, we want to take the waste hierarchy seriously by showing how EPR can prevent waste and not just stimulate increased reuse and recycling.

As a starting point, and in line with the beforementioned Eunomia report, we believe the aim of the scheme must be the reduction of environmental impacts. This is achieved most quickly and efficiently by reducing the EU’s production and import of new apparel and other textile products. But, for EPR to move towards a circular economy for textiles and not simply be an exercise in transferring costs, as the report formulates it, EPR must be designed smartly. One of the challenges with EPR, that the report points to, is precisely taking the waste hierarchy seriously, e.g., by not favouring recycling over reuse, ensuring that the environmental fee is high enough to have an effect on production volumes, and that the scheme includes the growing online shopping with direct imports.

The biggest challenge is overproduction: EPR must be designed accordingly

We are concerned that the measures proposed in the EU’s textile strategy (PEF, the Eco-design Directive and EPR) focus primarily on the product and its design together with end-of-life strategies (recycling), and thus not on the possible systemic changes that are pressing. In order to reduce the environmental impact of large volumes of textiles (fast fashion), measures are therefore needed that not only address the product’s design and strategies for prolonged- and end-of-life textiles, but also the number of products produced. If the EU is to achieve its goal of making fast fashion out of fashion, the means must be directed at factors that make fast fashion unprofitable. In extreme cases, we are talking about disposable products, in addition to the destruction of products that have never been used at all. It is not the design of each individual product that distinguishes fast fashion, which means that eco-design criteria will therefore not have the desired effect standing alone. A weakness of most of the EPR systems that have been implemented so far is that they do not take the issue of quantity seriously.

If the EU is to achieve its goal of making fast fashion out of fashion, the means must be directed at what makes fast fashion profitable: large volumes and rapid changes. The commission has been discussing a ban on greenwashing and planned obsolescence. In fact, fast fashion is planned obsolescence by definition. The clothes are not meant to last. Not because of bad quality or bad design, but because there is a new trend coming ever more often and faster.

The work on the development of PEF (Product Environmental Footprint) for clothing has also shown that it is extremely difficult to develop eco-design criteria for clothing, as the criteria for what constitutes good clothing are so varied and person-specific. Focusing on the product’s design does not capture the most important: whether there is an actual use for the product.

We believe that EPR can be designed so that quantity and speed are taken into account. This must be done by studying the use and disposal phases, and possibly also the quantity and speed of production. Those clothes that are used little and cost a lot to reuse/recycle will be the most expensive to put on the market.

If this is done and combined with sufficiently high fees, we ensure that one of the instruments in the textile strategy actually works, i.e., brings systemic change and is thus a true silver bullet.

The importance of the use phase

By the use phase we mean the time the product is in use. The longer this is, the less waste is created. Currently, textile use is an area with limited knowledge and data, however, in order for the EPR rules to have an impact on fast fashion and the related overconsumption, it is highly important, that we make sure that an EPR scheme considers use-related aspects. The use phase for clothing can be measured in the number of times something is used, or how long it is used. The latter is far easier than the former to measure. Instead of trying to guess which products will be used for a long time and modulating the fee on design parameters, it is possible to measure how long products from different (larger) retailers remain in use. Using “picking analysis” (a type of waste audit, an established method for analysing waste streams), sample analyses of textile waste and textiles donated for reuse, an average usage phase can be estimated.

The system will be far more accurate when the year of production is included in the mandatory labelling of clothing, a long overdue requirement. The time-lapse from when the product is put on the market until it goes out of use will give the manufacturers a score which is then multiplied by the volumes of the various brands or collections that suppliers put on the market. The modulation of the fee should take into account the producers’/brands’ average usage phase.

The brands that are not found in the waste streams will be exempt from paying a fee. This may be because the products are perceived as so valuable by consumers that they remain in their possession. Differentiations based on clothing categories should, however, be included as some garment types are expected to have longer use phases than others, e.g, a coat versus a T-shirt.

Reuse and disposal phase

When more textiles are to be collected for reuse and recycling, and more is to be done in Europe rather than in the Global South, the costs of these processes will increase. If more is to be utilised at a higher level in the waste hierarchy, it will also cost more. Much of what is not reused today could be reused if the clothes were renewed, i.e. repaired, washed or stains were removed, which in turn captures the reuse value of these products but at the same time carries a cost. These activities and related business models are currently underfinanced, and they lack profitability due to the associated high costs of manual labour and the overload of big volumes of low-priced and low-quality fast fashion items with no or limited reuse value. At the same time, certain textiles have a high value and can ensure a profit for collectors (e.g., resell business models where ca 5-10% of high-quality garments are sold on online platforms). It is important that all reusable textiles are given the opportunity to have longer lifespans, so if the EU is to aim to increase the reuse of textiles, preparation for reuse and repair activities must be financially supported by the EPR.

The same will apply to various forms of recycling: different products have different recycling costs. Some can be easily recycled; other textiles will not be recyclable at all or only if cost-intensive measures are first taken. As for the use phase, we, therefore, propose an average per brand based on how much the waste management costs. Those with a high reuse value and low cost of recycling will receive a lower fee, possibly an exemption in the end.

The modulation of the fee will thus consist of a combination of how long clothing from the brand is used on average and how costly better waste treatment is. Both evaluations can be made based on picking analyses that are repeated at regular intervals so that new brands, or improvements by already existing brands, can be captured. These analyses will also ensure increased knowledge about textile consumption and textile waste and will be important for statistics, research and regulation in the textile area. We have called this way of modulating the fee in an EPR system Targeted Producer Responsibility (TPR), which is described in ScienceNorway.no.

Production and marketing

The way EPR is usually conceived, the total tonnage of products placed on the market by an individual producer forms the starting point for the fee. But the quantities can also be used in the modulation of the environmental fee. It is possible to let those manufacturers who have many collections, a short timespan in-store for each individual product and also sell large volumes, incur a higher fee, which is then multiplied by the weight of what they place on the market. Proposals for such a fee modulation have been made by several Norwegian environmental organisations and can easily be combined with a TPR. It is also possible to use other parameters in the modulation, such as the proportion sold with reduced prices (the percentage that goes on sale), the proportion of returned goods, unsold goods, etc.

To summarise our proposal:

- The EU has a golden opportunity to ensure a systemic change for the better of its citizens and the environment.

- If we are to achieve the goal of reducing environmental impacts from textile production the quantities must be reduced. Less clothing is the prerequisite for each garment to be used longer, in line with the principles of the waste hierarchy and circular economy.

- The measures proposed in the EU’s textile strategy (PEF; the Eco-design Directive and EPR) all focus on the product and its design, and thus not on the systemic changes. EPR on textiles can, if desired, be designed so that it changes the business models of fast fashion by making it less profitable, and those clothes that are used little and cost a lot to be reused and recycled also become unprofitable to put on the market.

The above concerns and suggestions were a selection of many, and we are aware that a successful EPR agenda in the EU will include many more elements and key areas for coherent consideration.

Thank you for your time and attention.

Sincerely,

Ingun Grimstad Klepp

Professor of Clothing and Sustainability, SIFO, OsloMet

Jens Måge

Technical Advisor, National Waste Association of Norway

Kerli Kant Hvass

Assistant Professor in Circular Economy, Aalborg University

Tone Skårdal Tobiasson

Author, journalist, founder NICE Fashion and Board member Union of Concerned Researchers in Fashion