The interest in looking at the environmental consequences of clothes is growing. This was inevitable for two reasons: The clothing industry has been pointed out at as one of the worst polluting industries in the world. And we need to focus on all sectors to reach the climate and environmental goals.

The industry has therefore been sharpening its greenwashing knives for a long time and is ready to fight. Both authorities and the public lack the tools, however, to understand what actually matters in the new big green competition for “the most sustainable materials”.

The discussion about what is “sustainable” is conducted on false premises

We need to point out that already at the start, the very discussion of what is most “sustainable” is conducted on false premises. The most sustainable action is of course to not buy anything, and use what you already have in your closet. We need to increase the use of the materials and resources that are there already.

Take the example of red meat. Meat production produces more CO2 emissions than other foods, but this does not mean that all red meat has the same CO2 footprint. Nor does it mean that it is wise not to eat the more than 30,000 moose that will be hunted this fall in Norway. It is best to eat up what nature offers, not throw it away; as well as making sure local resources land on our plates.

In the same way, the clothes in our closet should find their way to our bodies, and as little as possible should be thrown away or purchased new, unless we truly need to.

The focus on apparel’s environmental footprint, however, often ends up in a rather fruitless discussion about the corresponding environmental footprint of various fibers. This despite the fact that it is not the production of the fibers themselves, but the production of the clothes with all the finishing-processes, such as dyeing, that have the largest impact. However, if one insists on comparing fibers, this needs to meet verifiable standards – and reflect the true environmental costs of said fibers.

How much clothes are used, is crucial to how sustainable they are

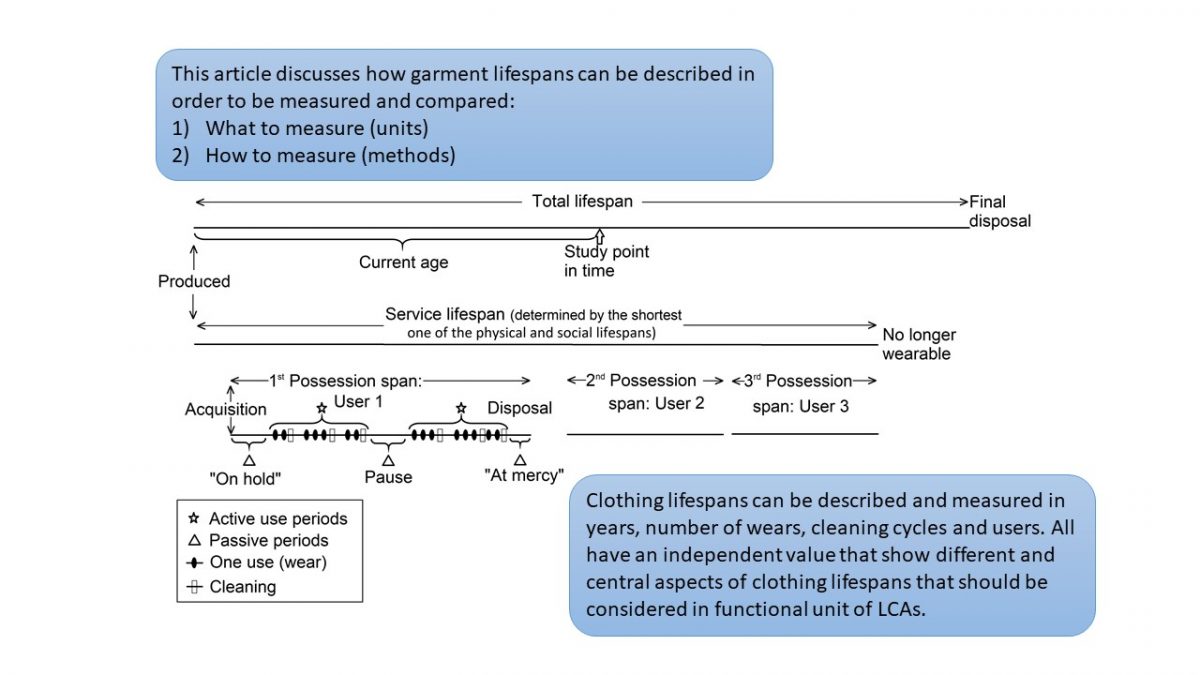

Comparisons of environmental impacts are done through life cycle assessments, or LCAs. The stages in production of clothing are examined and weighted in relation to different types of environmental impacts, such as CO2 emissions, water scarcity, eutrophication of water such as harmful algal blooms, resource depletion and so on.

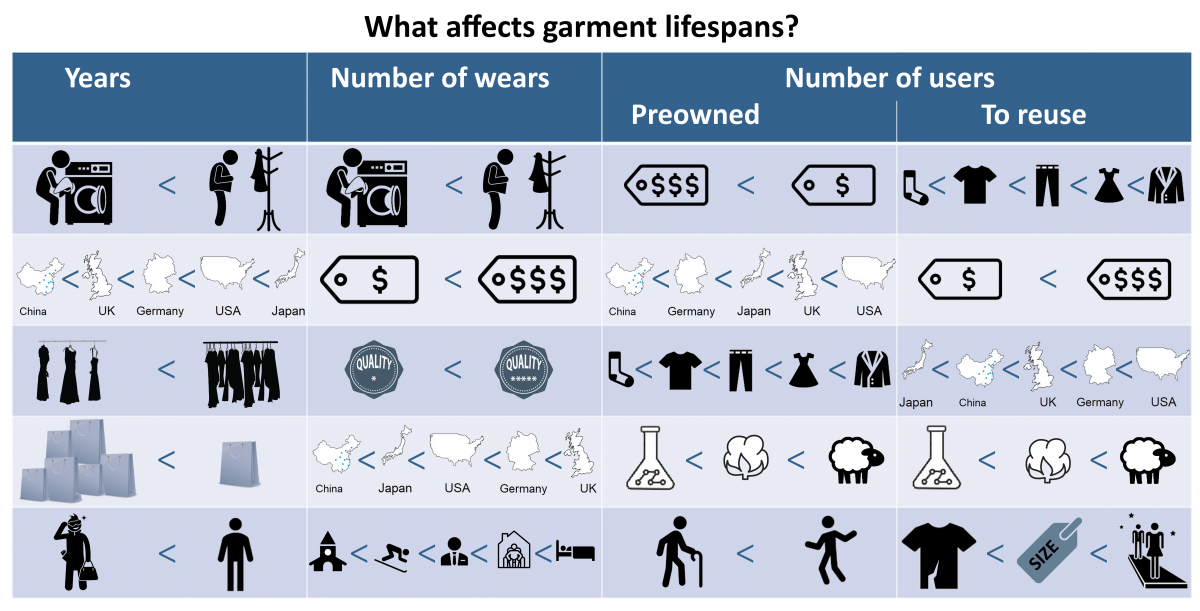

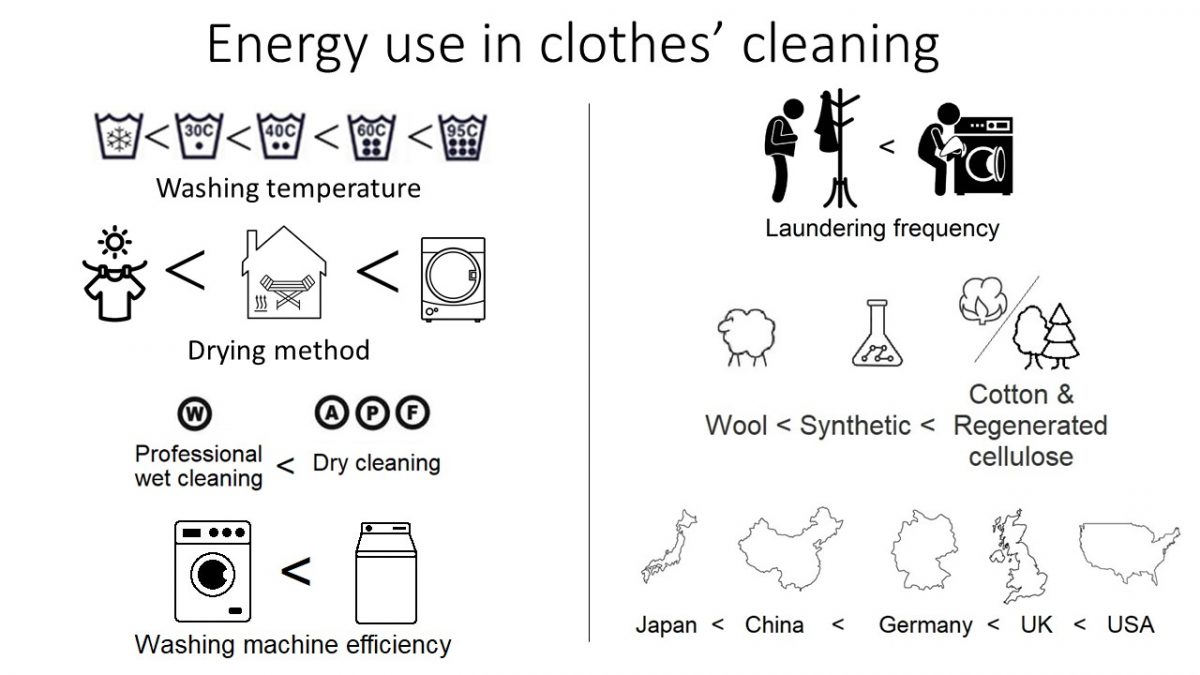

In traditional life cycle assessments these loads impacts are divided by the number of times the product is assumed to be used, so that “environmental impact per use” is the result.

If plastic bags are compared to textile shopping nets, the number of times they are used will be decisive for the result.

But there are actually few LCAs on clothing that include this crucial division. Without this, the life cycle assessments of clothing have major shortcomings in both method and data. To rectify this, Consumption Research Norway (SIFO) at Oslo Metropolitan University has actively contributed with its unique expertise on how clothes are actually used, the so-called use phase of clothing, together with LCA specialists from other countries. By including how a product is used, we avoid equating disposable products with those that last and are used for a long time.

We do not know enough about how clothes are produced

The second problem in this conundrum, is a lack of transparency and lack of reliable data. Much of our textile production takes place in China, and there is a lot that is hidden from view. It is thus not easy to find out exactly how much water is used in the cultivation of the Mulberry trees where the silkworms live, nor how much water is used in the actual production of the fiber and the textiles and many other important answers needed to conduct a proper life cycle assessment.

With little transparency, there will also be little knowledge. It thereby follows that few will be able to check if the datasets are reasonable when fibers and materials are ranked.

The third problem is a lack of knowledge about methods and perhaps also the willingness to take on the breadth of problems. So far, neither the textiles’ contribution to the spreading of microplastics, whether raw materials or fibers are renewable, nor whether they can be composted and thus are nutrients at the end of life, have been included in the LCAs.

This is how the tool for judging if the clothes are sustainable works

The tool most used by the industry is called the Higg Index. It is currently managed by the commercial company Higg Co, which has been spun off as a separate company from the group of industry players who call themselves the Sustainable Apparel Coalition.

This tool can and will potentially have a huge impact both on what is sold and how apparel is marketed. Under the Higg umbrella, there are several tools for members and others, who must pay to gain access to them. These tools are called MSI (Material Science Index), PM (Product Module) and FEM (Facilities Environmental Module). MSI measures the fibers against each other, FEM measures factories against each other and PM will give the product’s sustainability profile based on the first two. In addition, some impacts will now be entered on the use-phase, including from the on-going work done by SIFO on lifespan and care.

Based on all these scores, the manufacturer can play around with the tools to push the garment up, and preferably not down, on a “sustainability” scale.

This sounds perfect, right; since then the companies will strive to get the best possible score and then everything becomes more and more sustainable? And things are moving fast in this direction, because during the first half of 2021, online retailer Zalando and the Swedish giant H&M will use this scoring-system to tell consumers how sustainable the products they sell are. Already, 7 million customers have tested the system and learned how to purchase goods with a clear conscience.

Based on “ridiculously outdated and irrelevant” studies

There is still a terribly annoying fly in this soup. It is called accountable and verifiable data. “We use the best available data,” said Jason Kibbey, CEO of Higg Co, when he presented the new consumer-facing Higg initiative at the Copenhagen Fashion Summit recently. He added that as they gained access to more up-to-date data, they would of course adjust the scores in the system (wwd.com).

There’s just a small catch here, and that is that many of the studies that may be at the bottom of these scores are more or less impossible to get access to. They are behind a payment wall that neither you nor I can afford, and even then, they may not be made available. Those who have accessed for example the (one) study on silk, say it has so little relevance that is ridiculously outdated and irrelevant.

Considers polyester to be more environmentally friendly than wool

When we see that it is silk, alpaca, cowhides and wool that score the worst in the Higg Index MSI, while polyester scores among the best, there is reason to question the validity. The four materials mentioned are a small share of the world market, wool is only 1 per cent, alpaca and silk even smaller, while polyester represents 60 per cent (and is growing strongly).

Those who produce wool, silk and alpaca can quickly become even smaller when the large global actors, led by Zalando and H&M, are in the process of “improving their environmental profile”. It is a little too striking that polyester, which is the cheapest raw material that is the most profitable and which already makes up most of the textile industry, is considered one of the greener materials. Most of what is sold then automatically becomes “green”.

Chinese silkworms and Norwegian sheep farmers

The study Higg MSI bases its data on claims that far too much water was depleted and eutrophication was too high during production; however, this particular study aimed to show that in a specific and dry valley in India it was a bad idea to produce silk to begin with. This is the main reasons for the poor score just silk gets (veronicabateskassatly.com).

It will be the poor farmers in China, Cambodia and Laos who have never had their water consumption measured and who do not rely on irrigation, who based on this marginal study may have to find something else to live of rather than silk. In China the worms are also part of their protein diet.

In Peru, close to 100,000 poor families and half a million people, who depend on selling their alpaca wool on the world market are now in danger of losing their entire livelihood. Norwegian sheep farmers, who already have problems getting a fair price for their wool, will meet the same challenge. Also, all the wool that is today burned or disposed of all over Europe will remain waste no one wants. In an attempt to meet the criticism, the Sustainable Apparel Coalition decided last week to phase out the Higg Index MSI single-score on fibers in January 2021. The figures on which these single-scores are based will still live on in the Higg Index PM tool, which the apparel industry and consumers will view as the gold standard for the environmental footprint.

And you, dear customer, will encounter even more polyester in the stores in the future, alongside the ridiculous advice that you should use fewer virgin natural materials in order to be a responsible consumer.

Click here to read the op-ed (sciencenorway.no)