An Arts Practice Approach to Wardrobe Audits

Author: Wendy Ward, PhD Candidate, Sheffield Hallam University, UK.

Aim & Research Questions

My practice-based PhD titled “Enduring Fashion: Building Sustainable Clothing Practices Through Wearer-Garment Relationships”, uses art and design practice to explore people’s relationships with their clothes. The aim of the study is to investigate how these wearer-garment relationships might be leveraged to reduce the mass over-consumption and under-use that are currently prevalent in fashion.

The work is being guided by the following research questions:

- How often do people acquire and discard clothes, how many clothes do they own and how frequently are they used?

- What existing relationships do people have with their clothes?

- Can people be encouraged to develop an enduring relationship with their clothes?

- How do wearer-garment relationships impact clothing longevity and consumption?

Context

Fashion’s impact on people and planet has been known for the last three decades, but we seem to have become immune to the scale of our actions even when presented with the evidence and if anything things are getting worse, not better (Coscieme et al., 2022). It is clear that a change in approach is needed towards something more hopeful, relatable and empowering (UNEP, 2023).

Sustainability in fashion is reliant on individual behaviour and there is little point in designing a low impact, durable, recyclable garment if nobody wants to wear, keep and love it. This connection and relationship between people and clothes, which motivates the want to wear, keep and love is at the core of my work and I believe could be key to driving sustainable clothing practices.

I am inspired by the work of Richardson et al. (2015) on Nature Connectedness to inform my ideas about interactions with, and connections to, clothing and am using data visualization techniques to incorporate this into my creative practice. My work is grounded in a grass-roots approach to sustainability in fashion described by Alice Payne as “rewilding” (Payne, 2019), and a particular influence on my approach is Amy Twigger Holroyd’s Fashion Fictions research project that offered participants the chance to speculate on new social and cultural norms in clothing practices through deep material engagements with clothes.

Method

I am at the start of my research: one third into a part-time programme of study so the ‘method-in-progress’ I will describe has so far only been practiced on myself.

The Wardrobe Audit has been used successfully in academic research and described in detail in the original Opening Up the Wardrobe book. This practice is beginning to be adopted by the wider public, perhaps thanks to recent developments in AI and the growing use of self-tracking in all aspects of our lives leading to a growing interest in wardrobe logging and tracking apps. In my work I explore the possibilities of using a more analogue and creative approach to the Wardrobe Audit.

I began by auditing my own wardrobe and recording the results on a spreadsheet.

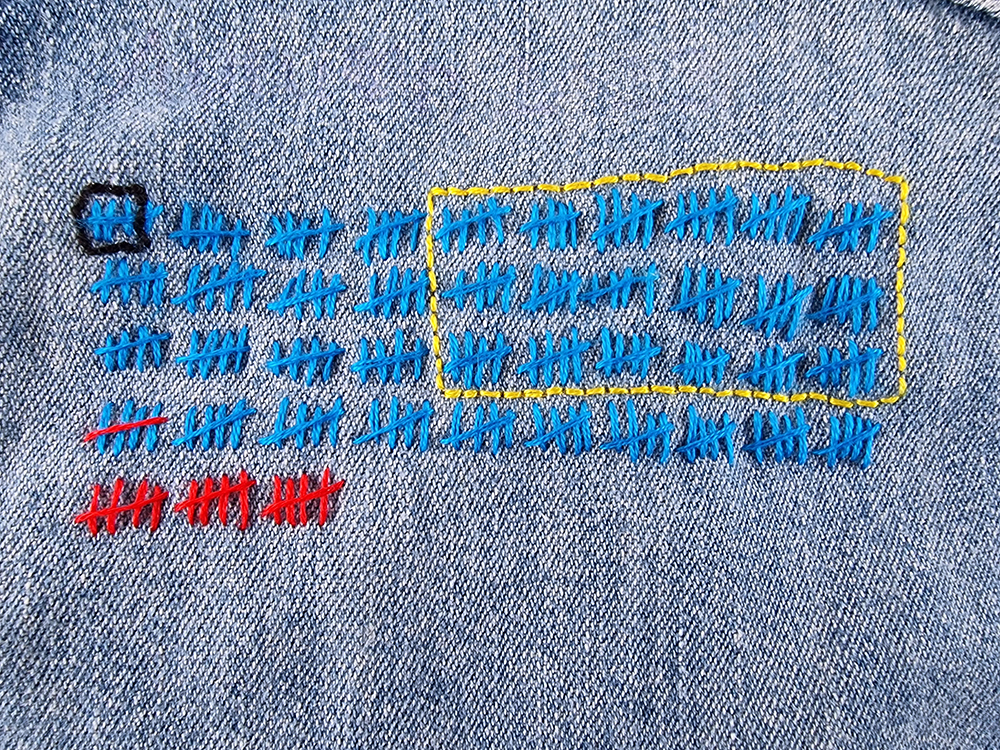

I found that the Information on a spreadsheet was too easy to ignore (especially when involved in daily clothing rituals of getting dressed and acquiring/disposing of clothes). I decided to represent the data in my spreadsheet in a more visual, but abstract way using needle and thread directly onto a garment. The resulting data visualization is a surface decoration which appears abstract to viewers and whose true meaning is known only to me.

I update my original audit at the end of each season and create a fresh visualization of the data. This led me to develop a similar method for logging and tracking my ongoing daily wearing habits. This method involves adding a stitch to garments from my wardrobe on each day that they are worn. Over time stitches gather on well-worn garments and are absent or minimal on less or never worn garments, resulting in a very visible and tangible way for me to confront my daily wearing habits over time.

My study has been ethically approved and I am currently recruiting participants for the collaborative phase. Informed by recent reports from WRAP and the Hot or Cool Institute identifying which demographic has the biggest impact on the planet in terms of fashion consumption, I am targeting the top 20% of earners in the UK who shop for clothes more than once a month.

As my study is practice-based and qualitative in nature, all data produced will be analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Early Insights

A strong sense of ritual and mindfulness is emerging from these tracking and auditing practices that I have now incorporated into my daily life. I am more aware of the extent of my wardrobe and how I use it (or not) and I am much more mindful of acquiring new clothes and how to discard those I no longer want to keep.

In early experimental workshops with volunteers while developing my method it emerged that experiential/sensory ways of researching clothing can expose gaps in existing knowledge. One such example is knowing what to do with clothing considered unfit for donation to charity; some of the volunteers I worked with had resorted to putting these clothes into the general waste bin (which in the UK is destined only for either landfill or incineration).

I hope that the results from my PhD can contribute towards improving the communication of the need for behaviour change around fashion consumption and clothing use, and ultimately provide some new tools for citizens to reassess the value of their clothing.

References:

Coscieme, L., Akenji, L., Latva-Hakuni, E., Vladimirova, K., Niinimäki, K., Henninger, C., Joyner-Martinez, C., Nielsen, K., Iran, S. and D ́Itria, E. (2022). Unfit, Unfair, Unfashionable: Resizing Fashion for a Fair Consumption Space. Hot or Cool Institute, Berlin.

Payne, A. (2019). Fashion Futuring in the Anthropocene: Sustainable Fashion as “Taming” and “Rewilding”. Fashion Theory, 23:1. 5-23.

Richardson, M., Hallam, J. & Lumber, R. (2015). One Thousand Good Things in Nature: Aspects of Nearby Nature Associated with Improved Connection to Nature. Environmental Values, 24(5), 603–619.

Twigger Holroyd, A. (n.d.). About. Retrieved January 10, 2024, from https://fashionfictions.org/about/

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), & United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2023). The Sustainable Fashion Communication Playbook – Shifting the narrative: A Guide to Aligning Fashion Communication to the 1.5-Degree Climate Target and Wider Sustainability Goals. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/42819.