[AD]DRESSING MUMMA: Longitudinal study of the pregnancy and postpartum wardrobe through the lenses of consumption, use and disposal

Authors: Dr. Zoe O. John, Dr Garrath T. Wilson, Dr Val Mitchell, School of Creative Arts & Design, University of Loughborough.

Aim of study

The research objectives were to understand the practices of consumption, use and disposal of clothing through a liminal period and whether this gives insight into ‘better’ practices of use. The research was explored through the physical and emotional changes of pregnancy and the approximate year following birth. The focus of the study was to see if an individual’s sense of physical and emotional comfort, including their sense of identity, changed over a liminal period, and whether these were compromised or bolstered through what an individual wore.

The research questions driving this were:

1. What are the drivers of the consumption, use and disposal of clothing during pregnancy and the postpartum period?

2. Can you dress ‘sustainably’ during pregnancy and postpartum?

3. Can you dress ‘sustainably’ whilst supporting your identity during pregnancy and into the postpartum period?

Method

This was the fieldwork for my PhD research, a constructivist study with a feminist lens (Letherby, G. 2003), the research was conducted with a bond of five women over nearly two years, inspired by my experiences of dressing through pregnancy and the postpartum period and through discussions I had with others going through a similar period. As the project developed it seemed obvious to me that I needed to be studying participant ‘wardrobes’ and using their clothes as a catalysis for the exploration of the themes I wanted to examine.

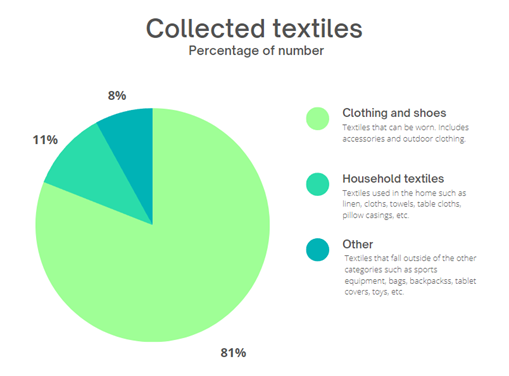

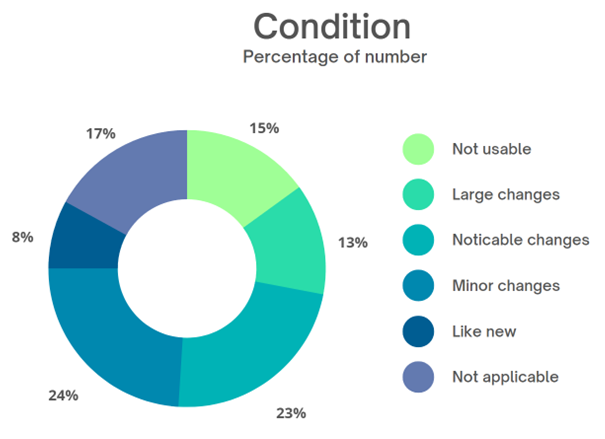

I visited my participants 4 times (twice in pregnancy and twice postpartum). Each visit looked at the same three themes (consumption, use and disposal). By invitation we would sit by their ‘wardrobes’ (these could also be a chest of draws, hanging rails or a whole room) and participants would talk through what they were or were not wearing, where it came from (purchase, gifted etc.) or where it was going (passed on again, the charity shop, waste etc.), how it made them feel and ultimately why they responded as they did. I recorded our conversations on a Dictaphone and took photos of the clothes they told me about, as well as their ‘wardrobes’.

Participants were recruited through social media and word of mouth. They were based in the South East of England. Initially, 8 participants were taken forward, but for the final thesis only data from 5, all first-time full-term pregnancies, participants were used. No specific characteristics were asked for in the recruitment process, but they all ended up being in a committed relationship, Caucasian and with a comfortable socio-economic background.

I did play around with ideas around using visualising tools etc. and took these into the wardrobe studies, but the data was already so rich, that they were not needed.

I used thematic analysis as popularised and researched by Braun and Clarke (2006 to 2021) with support for the process of analysis from Taylor-Powell and Renner (2003). I found the lack of information on how people analysed their data frustrating, so I included a section on the literal step-by-step analysis process in my thesis (3.7.1, John, Z.O. 2012).

One of the nicest things about conducting this research was that almost every time I shared what I was doing with other women who had been pregnant (some many years previously), they regaled me with stories of their own experiences and reflections of dressing through pregnancy, and those first few months that follow it, and both the internal and external challenges in locating ourselves with help and hindrance from the clothes we wear. I believe that sharing real stories is the essence of the human experience and a segue to understanding how we can better design for and serve the world around us.

The data generated was used to inform my PhD research and academic papers based on the thesis.

You can follow the methodology and carry out the same mechanics, but what became clear to me was that the outcomes from this exploration were shaped by my experience, the specific experiences of my participants, and the relationships that we developed over nearly two years of wardrobes studies, and just as every pregnancy and every baby are different, so too is every experience of dressing through pregnancy and into the postpartum phase. However, this research does not provide any data on the consumption, use or disposal of clothing for different socio-economic, cultural or geolocated studies. It also does not take into account practices during liminal times such as living, dressing and pregnancy through a global pandemic, nor how identity was constructed through clothing when most of us were at home in our pyjamas till noon. Although there was research conducted within this space, this project places itself firmly in a pre-Covid time. However, it acknowledges that it is likely that aspects around the ‘what and how’ of our practices of dress, and our relationship with clothes, may have been changed through the experience we had during that time.

Wardrobe studies can offer several insights for understanding sustainable practices and emotional attachment for better practices, but they can also offer insights into, among other things, external factors such as seasonal or economic conditions and the impact of global events.

This was the first study to explore what it means to dress sustainably through pregnancy and the postpartum period and as such offers a number of opportunities for continuous exploration. The results could be used to support design work, business development, systems or services or used as a springboard to further academic studies. See 8.4 John, Z.O., 2021. for an extended number of prospects identified.

Wardrobe studies are an intimate exploration tool and that as such they should be treated with the utmost respect and sensitivity. However, this also means that they are rich with life experience and therefore can offer deep insights into the human experience.

My experience is that people like talking about the clothes they wear and the stories behind them. What happens as they tell these stories is a sub-narrative that offers insight into why we make the choices we do and therefore, how we can work with, rather than against, our human nature, to move towards better practices of consumption, use and disposal.

References:

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) ‘Qualitative Research in Psychology Using thematic analysis in psychology Using thematic analysis in psychology’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), pp. 77–101.

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2021) ‘One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis?’, Qualitative Research in Psychology. Routledge, 18(3), pp. 328–352. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238.

John, Zoe Olivia (2022). [Ad]dressing mamma. Fashion practices of consumption, use and disposal at the liminality of pregnancy. Loughborough University. Thesis. https://doi.org/10.26174/thesis.lboro.20272389.v1

Letherby, G. (2003) Feminist research in theory and practice. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Taylor-Powell, E. and Renner, M. (2003) ‘Analyzing Qualitative Data (G3658-12)’. Available at: https://learningstore.uwex.edu/assets/pdfs/g3658-12.pdf (Accessed: 1 March 2018).