New study highlights how cultural and local contexts shape the longevity of clothing

A new open-access article in Scientific Reports (Nature Portfolio) explores how communities across the globe define and practice garment durability. The study, titled “Understanding garment durability through local lenses: a participatory study with communities across the globe”, was led by PhD candidate Hester Vanacker and co-authored with an international team of researchers: Andrée-Anne Lemieux, Kirsi Laitala, Michelle Dindi, Sophie Bonnier and Samir Lamouri. Kirsi Laitala is one of Hester’s supervisors and contributed to this article through Lasting project.

Addressing global challenges in fashion and sustainability

The fashion and textile sector is highly resource-intensive industry. The overproduction of low-quality garments contributes significantly to environmental degradation, particularly in the Global South. As policymakers and industry actors work toward more sustainable and circular systems, garment durability – how long clothes last and why they are kept or discarded—has become a key issue.

While durability is often understood in technical terms such as fabric strength or wear resistance, this study broadens the concept to include social, cultural, and local dimensions. It asks how people in different parts of the world define, value, and maintain the longevity of their clothing.

A participatory global study

The research team employed Participatory Action Research (PAR), conducting semi-structured interviews with 73 participants across the garment value chain in France, Ghana, Indonesia, Norway, and South Africa. The participants represented a diverse range of roles, including artisans, designers, second-hand sellers, educators, activists, and members of NGOs.

This inclusive approach allowed the researchers to capture perspectives from both the Global North and the Global South, offering insight into how local conditions, such as climate, culture, and available materials, influence the meaning and practice of garment durability.

Eight trends shaping the understanding of durability

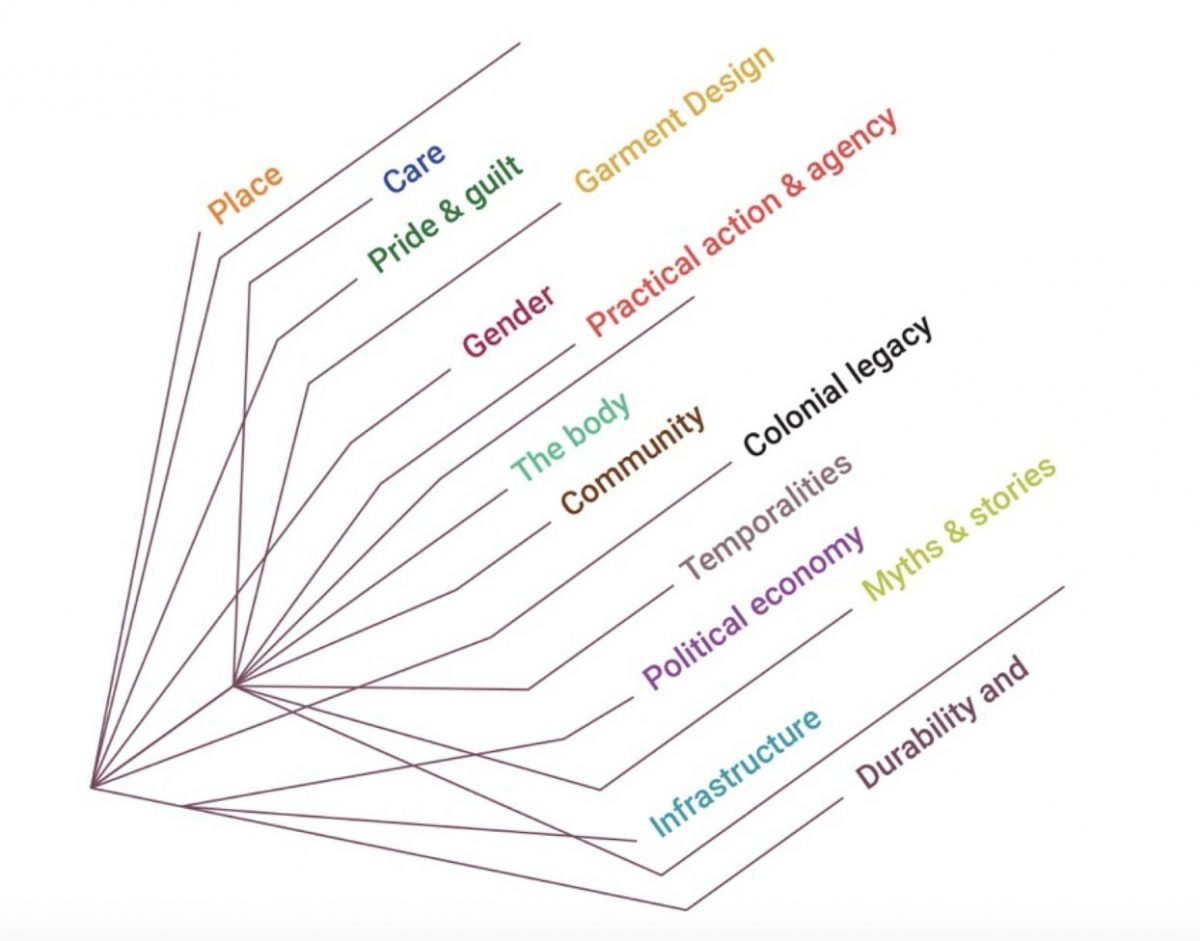

The study identified eight interconnected trends that illustrate how notions of “durability” and “local” intersect:

- Quality is preferred over durability – Many equate durability with quality and craftsmanship.

- Garment durability is dynamic – Clothing gains and changes value through care, repair, and reuse.

- Price and brand influence perceptions of durability – Branded or expensive garments are often assumed to last longer.

- Local refers to geographical proximity – Locally produced and used garments carry added meaning and value.

- Local involves value creation – Garments that support local livelihoods and skills strengthen communities.

- Local touches tradition – Traditional garments reflect heritage and collective identity.

- Traditional garments and textiles are more durable – Cultural significance often encourages better care and longevity.

- Local contexts influence durability – Climate, culture, and social practices affect how long garments stay in use.

A framework for more inclusive policies

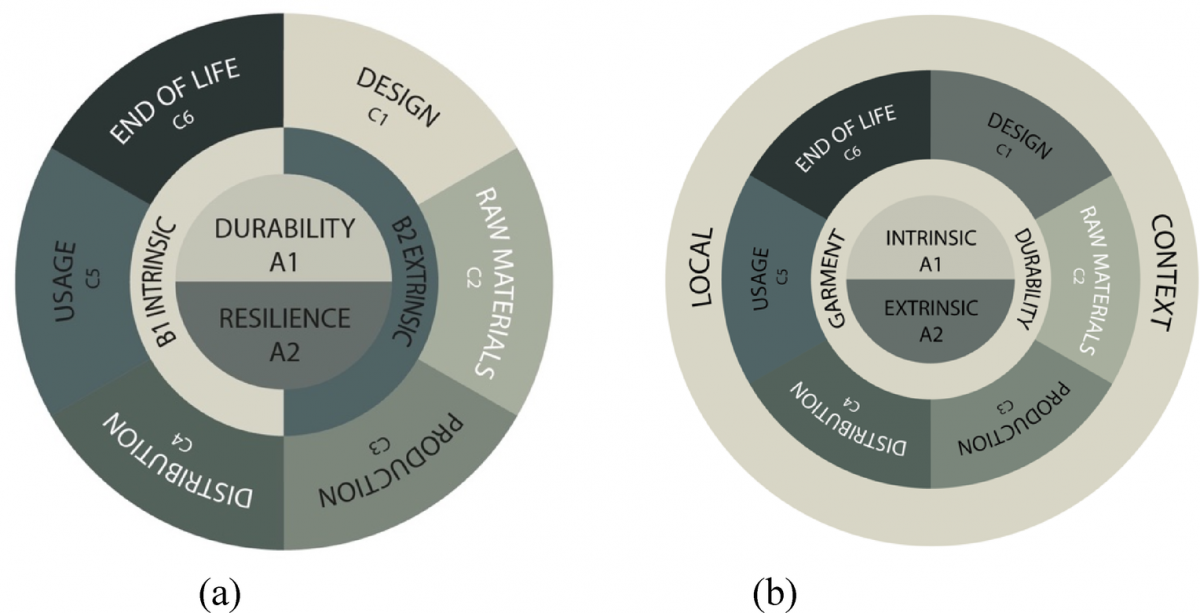

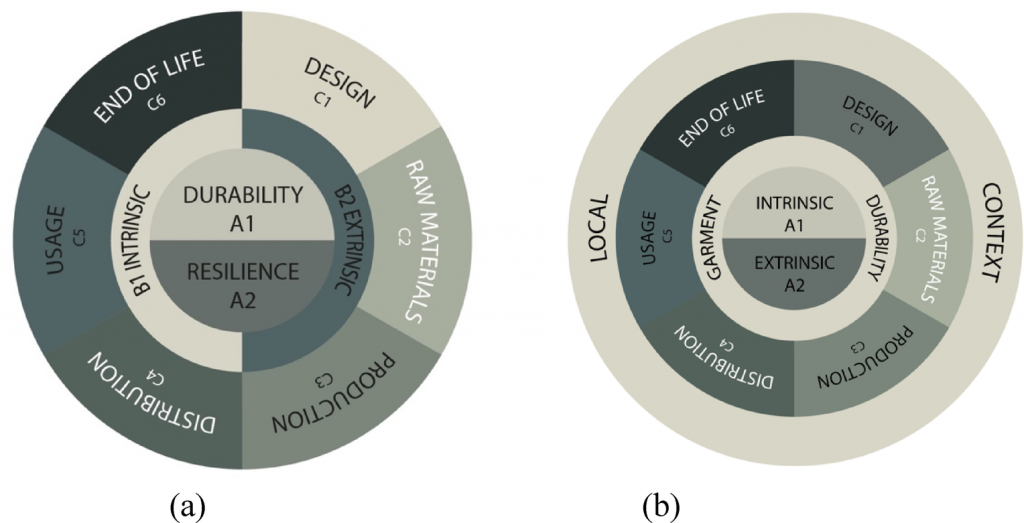

Based on these findings, the authors propose a revised framework for garment durability that integrates local contexts alongside technical and environmental considerations. The framework emphasizes the need for context-sensitive approaches in emerging sustainability regulations and industry standards.

“Policies developed in the Global North often have unintended consequences elsewhere,” says Hester Vanacker, “Our findings show that a meaningful understanding of durability must include the perspectives and practices of local communities worldwide.”

Towards a locally grounded circular transition

By highlighting the connections between global trends and local experiences, the study contributes to a more holistic understanding of durability in the context of circular economy and sustainable fashion. It calls for legislation and industry practices that respect cultural diversity and the lived realities of garment users and producers around the world.

The research also demonstrates how participatory methodologies can bridge academic and community-based knowledge, ensuring that sustainability transitions are both equitable and grounded in real-world contexts.

The full article is available open access via Scientific Reports (rdcu.be).

Reference

Vanacker, H., Lemieux, A.-A., Laitala, K., Dindi, M., Bonnier, S., & Lamouri, S. (2025). Understanding garment durability through local lenses: a participatory study with communities across the globe. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 34962. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19087-3