EU’s fear of addressing overproduction uncovered in eye-opening research

A new research article in Journal of Sustainable Marketing address EU’s Textile Strategy’s blatant avoidance of the volumes issue, and raises the question of why.

In the Journal of Sustainable Marketing, a new article penned by Irene Maldini and Ingun Grimstad Klepp, The EU Textile Strategy: How to Avoid Overproduction and Overconsumption Measures in Environmental Policy, takes the bull by the horn.

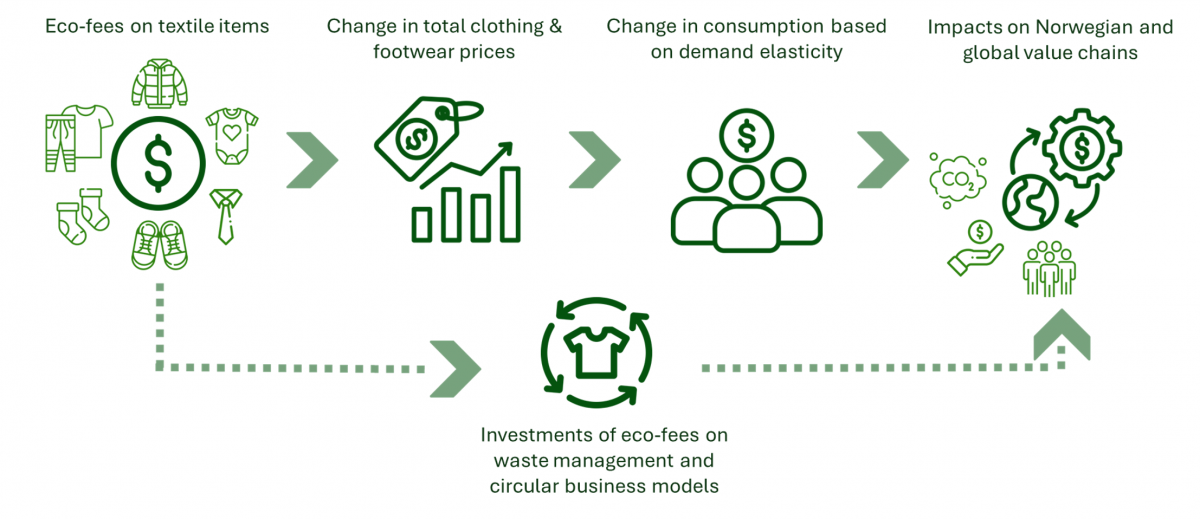

The analysis, which was just published, shows how the focus on product durability avoided addressing production volume reductions measures, leading to the exclusion of marketing-oriented regulation (applied to price, frequency of new products put on the market, product placement with influencers, advertising including social media strategy, etc.), which could have actually significant effect in tackling overproduction and overconsumption.

No volume-related questions

Instead, in the open hearings, no questions were asked that were volume-related, only related to durability (with the exception of overconsumption being mentioned once). In the answers, however, volume-related wordings are common – however, in the summary of the feedback, everything about volumes again disappears.

The article is based on the analysis of public documents and interviews with participants of the policy making process, the study unpacks the factors that enabled such a decision, and how it was integrated in the final document.

In sum, the analysis suggests that measures aimed at reducing production and/or consumption volumes were out of the scope of the Textile Strategy already from early stages. The public consultation process was designed, conducted, and analyzed in a way that ensured this exclusion, despite the efforts of some stakeholders and many survey respondents in bringing this issue to the table. The final document does not propose any mechanisms to check and ensure that these have an effect in volume reduction or on the environmental impact for that matter.

Only three peer-reviewed scientific articles

The analysis rather shows that by focusing on product durability, an explicit aim to reduce the volume of clothing was avoided, leaving potentially impactful marketing-related measures out of the scope. The study also uncovers that of the 56 different publications cited to provide the data base for the Textile Strategy, only 3 are peer reviewed scientific articles.

And this is not because there is no knowledge available on textiles and the environment impact from researchers. However, in a marketing journal, we think our perspective from consumption research ploughs new ground.

Thematically, there is a lot of overlap between consumer research and marketing research on consumption. Yet there is little cross-citation and little collaboration. This is probably related to a certain mutual skepticism. Consumer research is about taking the consumer’s position, while marketing is the opposite – at least initially, with the desire to sell something and later change consumers in one way or another. Therefore, it is extra gratifying that we have managed to overcome this barrier by publishing in a marketing journal. With great help from Diego Rinallo, Doctorate in Business Administration & Management, Bocconi University, Milan, Marketing Department. His input has been invaluable.

The more we have seen the limitations of product perspectives (such as making products “repairable” and the ideas of “educating” consumers to act “sustainably”), the clearer it becomes that marketing must also be included in policy. We need knowledge about how it works and how it can be limited.

The EU, like Norway, is proud of its democracy. In the mapping of why policies develop as they do, and how and by whom decisions are made, it has been surprisingly difficult to gain insight. As the article shows, there was a lack of written documentation about the processes, a reluctance to be interviewed (although no personal questions or questions about opinions were included) and anonymity was ensured.

Sensitive stuff?

How are decisions made and are they really this sensitive to scrutiny? This begs a bigger question perhaps media should ask.

This raises questions not only about why transparency is not valued more highly in democratic countries/regions, but also about the relationship between the research community and policy.

The article sheds light on this relationship directly, and an analysis of what the EU strategy refers to, i.e. what kind of knowledge is used as a basis.

As first author, Irene Maldini reflects: “It has been an adventurous journey to develop my work into this area, and to experience the double role of trying to influence policy building on scientific knowledge (advocacy) and at the same time analyzing the processes of policymaking as an outsider (research). The former has also enabled the latter, because resistance to acknowledge the limits of the planet and economic interests in policy making processes become so clear when you are trying to bring the sufficiency agenda forward.”

To access the open access article, click here.