New consultation on PEF: Feedback delivered

We have submitted feedback for the Product Environmental Footprint Category Rules. A total of 355 responses have been submitted with a total of 5125 comments. You had to fill in an Excel form, which was a bit challenging to navigate. We have therefore extracted the answers from the Excel sheet and created a document that is easier to read, click here.

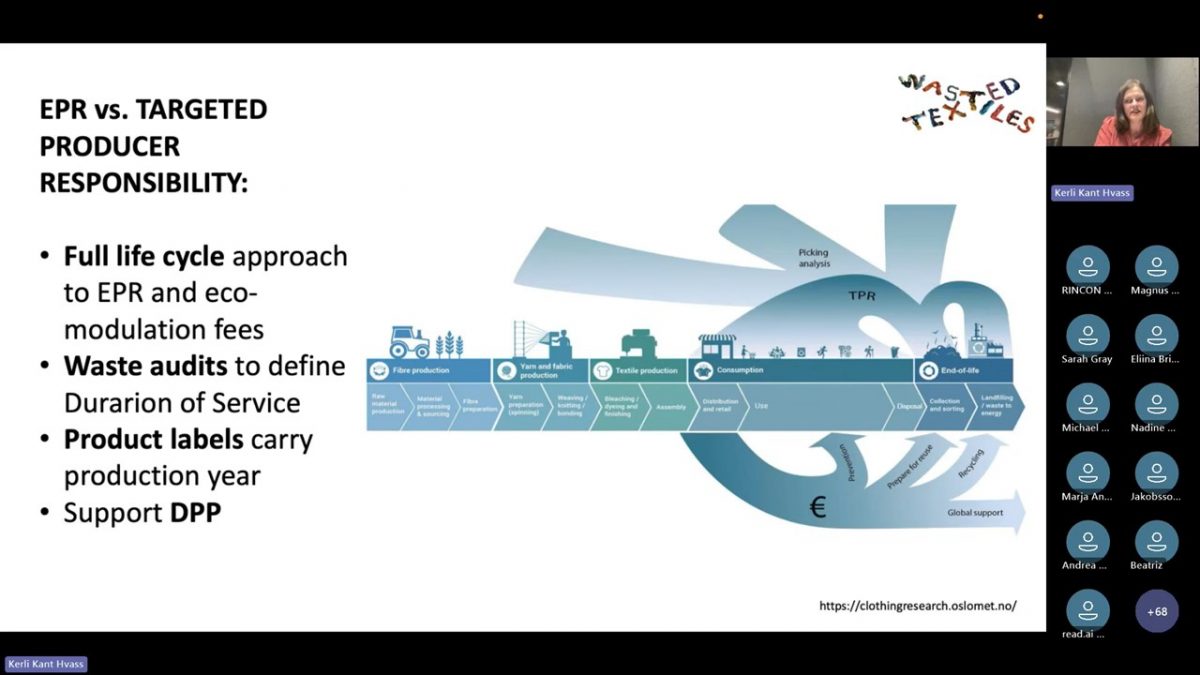

PEF is intended to be used for all products, but this consultation concerns clothing and footwear. The aim has been a label for everything put on the European market, but the plan has been scaled down to a tool that will “only” be used to document green claims. The calculation tool itself, however, is the same. Products put on the market can be compared with a “normal” product in the same category. 13 categories have been created to cover all types of clothing and shoes.

The only of these categories where fiber or material is mentioned are under sweaters, where wool is mentioned (but not alpaca) and jackets/coats, which include leather jackets. For each of these “phantom garments” what is measured and weighted is very different, and this makes it hard to understand what you are actually comparing against. For example, “land use” (how many kilograms of fiber you get per square meter) is the most important factor for sweaters and “midlayers”, not for any of the other product groups. What the logic is for this, is impossible to find out in the many and long background documents.

Stumbling blocks

The consultation process itself has been anything but democratic, with stumbling blocks on all levels. Just getting into the EU database to deliver a response has been difficult without a black belt in passwords and apps, and as mentioned, you had to read hundreds of pages of background material and refer to exactly which document, which chapter and which line was being addressed. But perhaps the worst thing is that the documents don’t really say what the result of all the various data-inputs will actually be. Before we submitted the response, everyone could participate in a webinar where we were told that, for example, complaining about microplastics not being included would fall on deaf ears because the very tool underpinning PEF (LCAs) do not allow any new parameters to be added.

So even though the EU Commission had instructed the working group working with PEF for clothing and shoes to include the problems surrounding microplastics, we were told that there was no point in pointing out the obvious weakness that this has not been done. The fact that one can voluntarily say something in the product information about microfibres (not microplasics specifically) does not solve this major problem.

Understanding the functional unit

Another problem is the weak understanding of the functional unity. This is the very foundation of LCAs, for them to provide meaningful information. This means that the thick, warm Devold sweater that you wear all winter in Norwegian wool will be a true environmental disaster (Norwegian sheep take up an incredible amount of space when they graze) compared to the thin acrylic sweater that you bought on sale and are considering throwing away having discovered that you get an electric shock every time you pull it over your head. How long and how much clothing is worn is important for the environmental impacts in an LCA, but here too PEF falls short. This is particularly where we at SIFO have contributed to bring out knowledge and methods that can be used to correct this. Read more here.

Biodiversity does not count either, which the sheep contribute to in the grazed rangelands. Nor that they contribute to carbon storage in the soil. All that counts are the negatives, even when in the case of land use, the wide space is actually a positive! In connection with the consultation, there are many small producers of wool and other natural fibers who have responded, because they are scared that their livelihood will be evaluated as “red”, not “green”. The question then is whether the EU will listen, or whether they plan to override common sense and the need to reduce actual environmental impacts, and still introduce PEF for clothing and footwear to show action and justify all the time and resources that have been spent to develop the system.

SIFO has delivered a response. Let’s hope it helps.