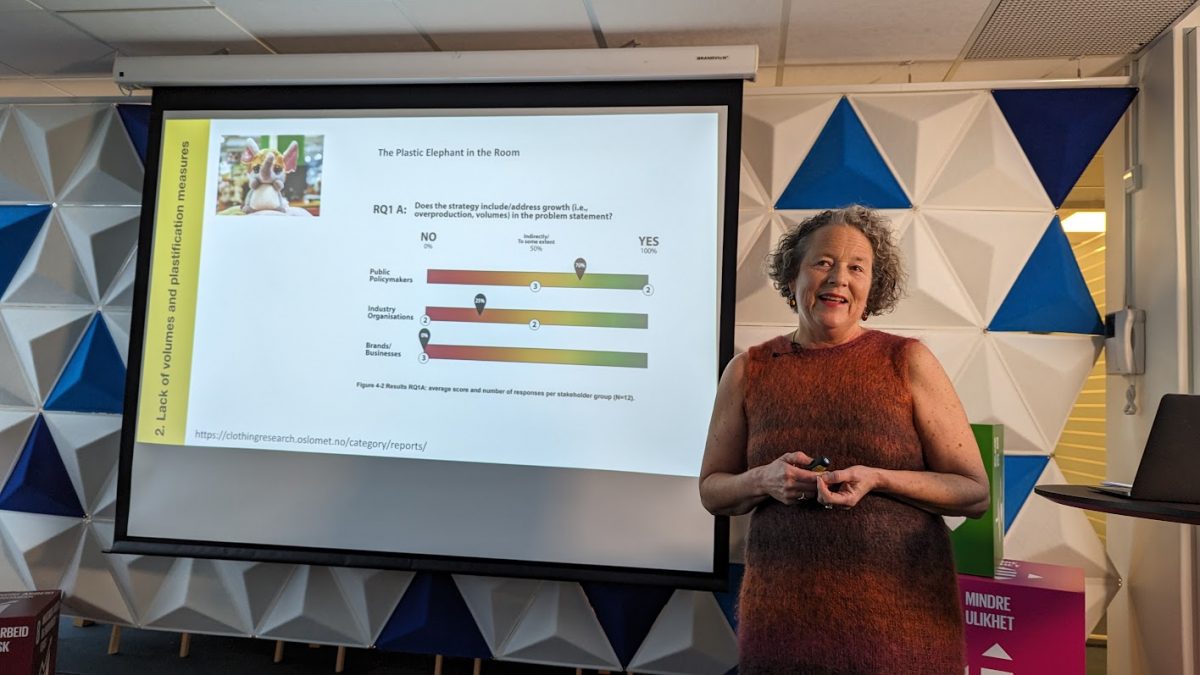

Volumes, policy measures and Targeted Producer Responsibility all fitted into discussions the week before Easter, where some of us jumped back and forth between Webex, Zoom and Teams, recordings and live webinars. The take-aways are that several policy tools are mired in antiquated ideas that seriously need updating from research, and that the conversations around volumes and sufficiency are what actually can drive change.

STICA’s Climate Action Week coincided with intense webinars from EU’s Joint Research Center on ESPR’s stakeholder review and also PEFCR for apparel and footwear’s open hearing, presented by the Technical Secretariate’s lead. Yes, it was dizzying, but most importantly, Targeted Producer Responsibility and questions surrounding how EU actually plans to address the issue of volumes and degrowing the sector did got airplay.

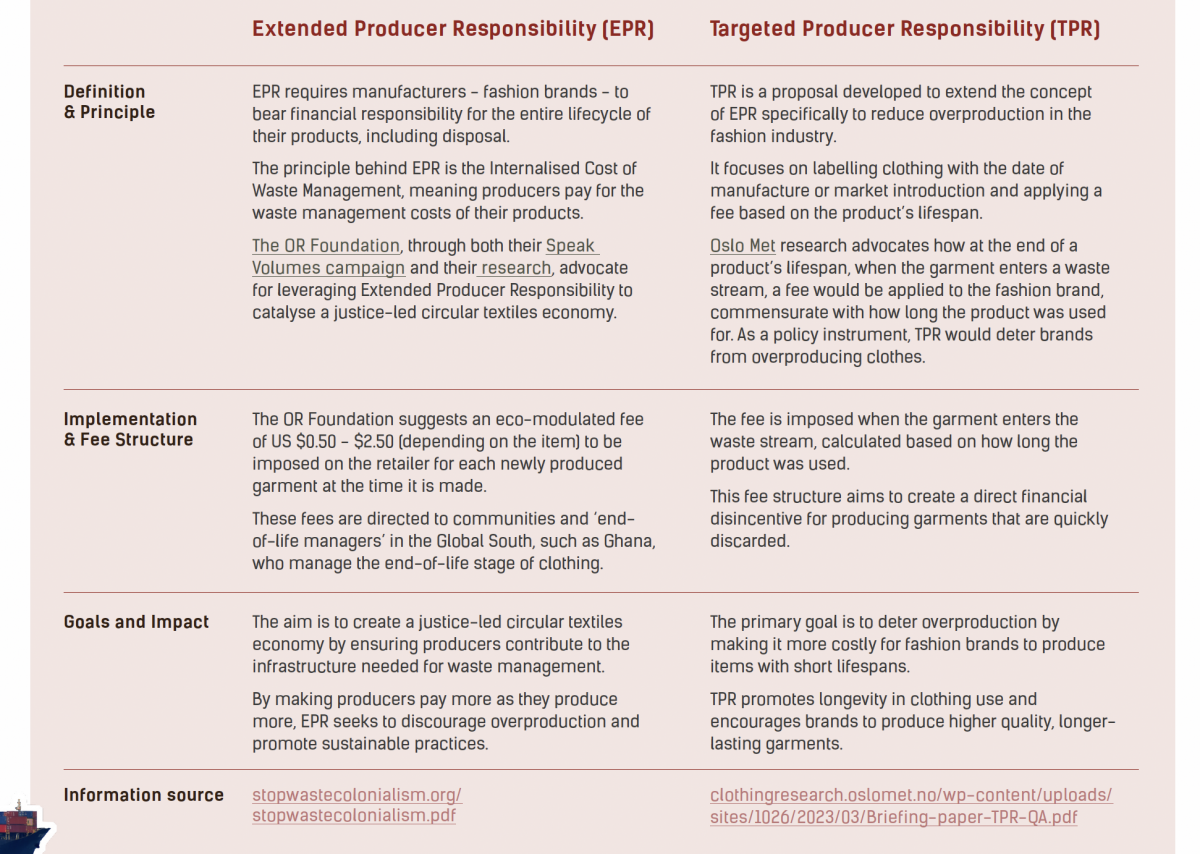

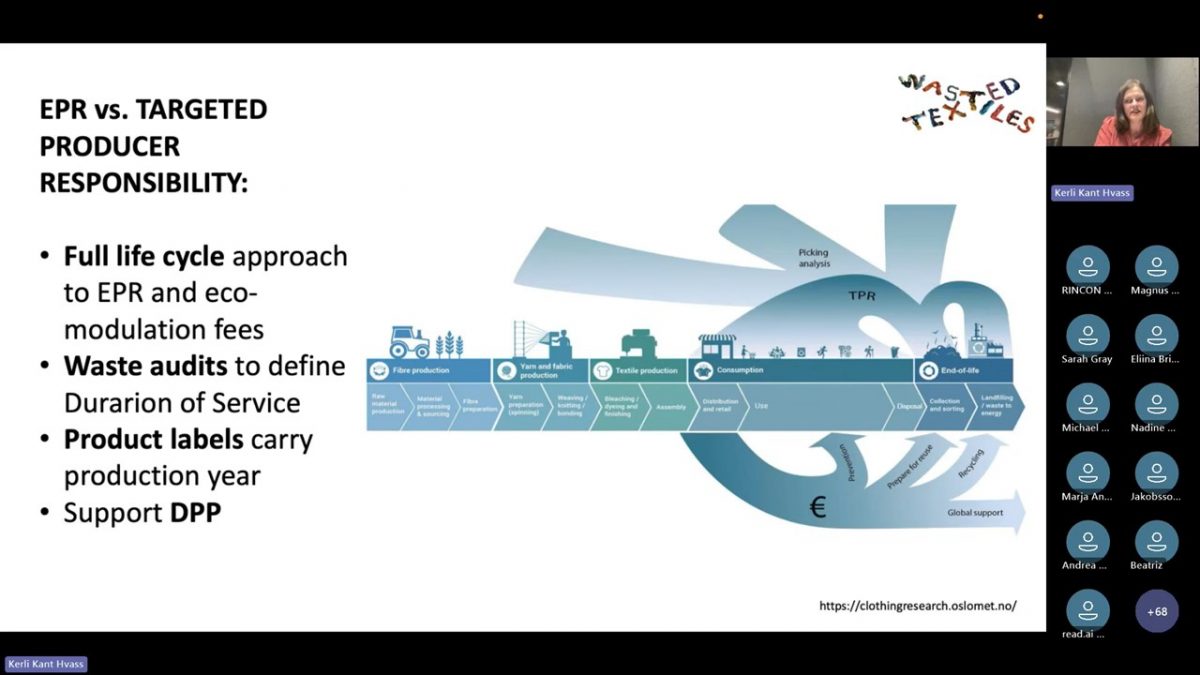

Kerli Kant Hvass, who is one of our Wasted Textiles partners, presented Targeted Producer Responsibility during the session on the obstacles facing new circular business models during STICA’s Climate Action Week, hosted by Michael Schragger from Sustainable Fashion Academy and lead for Scandinavian Textile Initiative for Climate Action (STICA). In the session Circular Business Models Are Critical for Climate Action – So What Is Preventing Them from Becoming Mainstream? she explained the concept, and continued her argument during the panel discussion towards the end:

“Focusing on the product and assuming this will result in sustainability has serious limitations. Instead, collecting data in the waste streams, and establishing if a product has been used for half a year or for ten years, actually establishing its duration of service (DoS), can give the database for modulating fees.”

TPR got nods

We noticed that Maria Rincon-Lievana, from the EU Commission and DG ENV nodded a lot when Kerli repeated this. Sarah Gray from UK’s WRAP, who is wrapping up a PhD on to what degree circular business models actually have climate and environmental impact, wholeheartedly backed Kerli’s call for dating products in order to gain data on the actual DoS of products for comprehensive LCAs.

Sadly Paola Migliorini, also from DG ENV, did not hear when Luca Boniolo from Environmental Coalition on Standards (ECOS) said the following in the session on The Legislative Race Is On: Legislation & Regulation in the European Union (we can only hope she reheard the entire session later):

“Labelling regulation presents an opportunity (…) for instance introducing the production date on the label (…) we can know how long the product has been circulated at the end of life. If we do waste audits, we can estimate the DoS to understand was it used to 10 years or was it used for two weeks and then it was discarded and it can also support consumers in knowing that they have the right of a legal guarantee from the purchase date of two years during which if the product fails under normal circumstances, they have the right of it being repaired for free.”

He said much of the same during the session on Sufficiency, To Green-growth, Overconsumption & Degrowth: Can Sufficient Emissions Reductions Be Achieved in the Current Paradigm?

“EPR can for instance be based on how long the product was on the market based on waste audits and the date of production, and thus we can modulate who will have to pay a higher fee. We need to incentivize the reduction of the volumes placed on the market.”

This is the whole idea behind TPR, and even if Luca did not specifically mention TPR, he was voicing the principles behind it.

Old-fashioned or not fit for purpose, or both?

So, what is old-fashioned about the approach the policy-makers are taking? What are the tools that are not fit for purpose?

As it was ESPR and PEFCR we were lectured on the same week, the following thoughts arise.

ESPR (Ecodesign for Sustainable Product Regulation) clearly is based on the faulty assumption that 80% of a product’s environmental impact is decided in the design phase. So, it is intertwined with predicting for example durability, repairability, recyclability and thereby assuming DoS. The problem is, as SIFO research shows, only one-third of textile products or apparel go out of use because they are used up, so if ESPR is going to eco-modulate EPR fees (which seems to be the idea) this will be based on pure guess-work, or what could be more diplomatically called predictions.

TPR suggests the opposite, building the eco-modulation on what becomes waste prematurely and modulated ‘against’ what captures value in the new business models, as Kerli so well described in her presentation.

The hen or the egg?

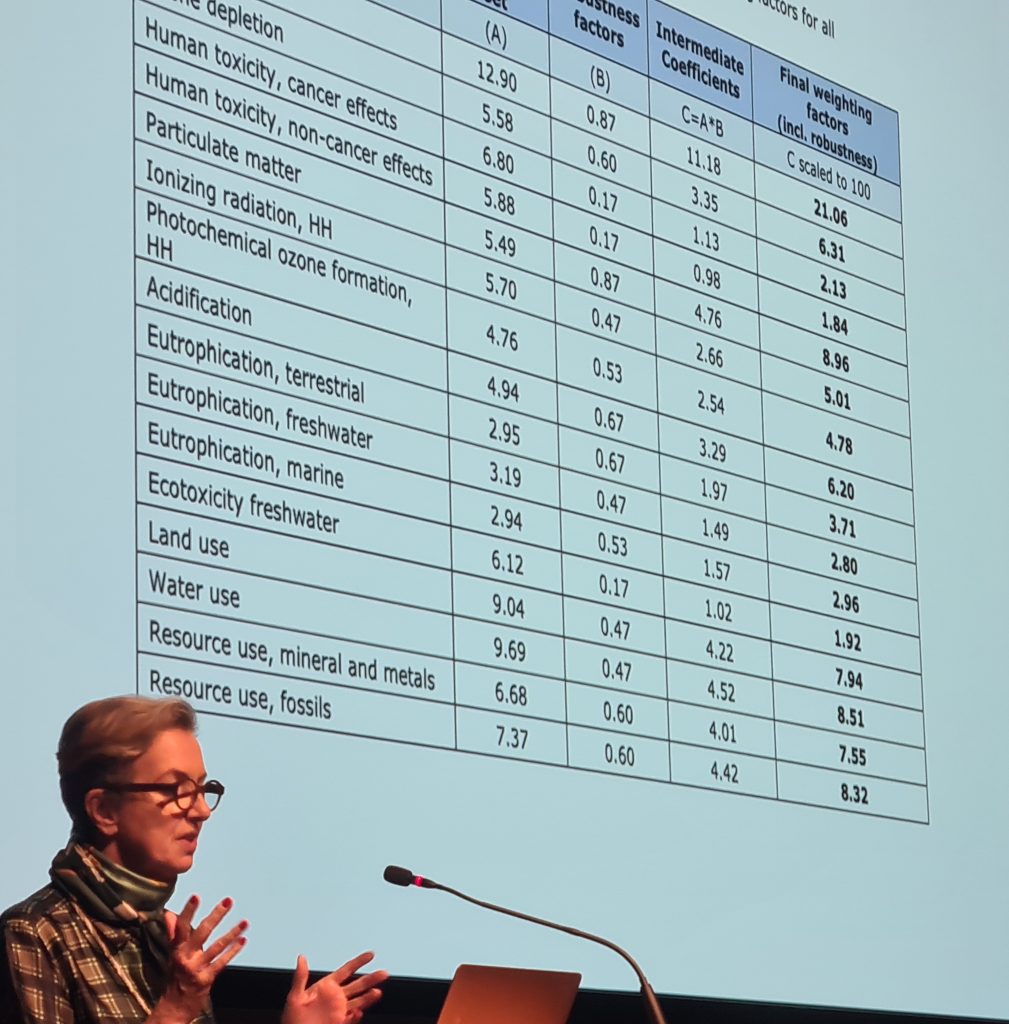

For PEFCR (Product Environmental Category Rules) the problem is that they are meant to underpin ESPR, but JRC have actually not decided if they are fit for purpose, they said as much in their presentation. So, currently PEF seems to be in limbo, perhaps only fit for Green Claims (Baptiste Carriere-Pradal said as much in his presentation, but also hinting that ESPR would have to use PEF).

PEF is not aiming to be a consumer-facing label, only a set of 16 “frankenproducts” (12 for apparel, four for footwear) which you as a company can compare your product to, and say if your product is “greener” than the “frankenproduct” based on very strict LCA parameters. The data-base that these parameters are resting on, have serious data issue, and may be why France when presenting their “amost-PEF-compatible” label, have taken out one of them (physical durability), In addition, France also is not making GHG emissions the most important parameter – counting for 1/4th of the ‘score’, which PEF currently does.

The main problem, though, is understanding. Consumers understanding what and why.

Simply: In ESPR there is a demand for recycled content, and this is heavily stressed. During the sessions, I asked simply “why?” and presented the latest IVL report with a 1.3% climate reduction for large-scale recycling in the EU. What also surfaced during the week was that only 11% of EU’s population want recycled content. So, win-win or lose-lose to demand recycled content?

Apparel for real life or for bureaucratic purposes?

The issue then feeds into PEF, and how the scores of the “frankenproducts” actually have meaning when talking about real life. Why are stockings, socks and leggings the same “frankenproduct”? What are sweaters actually – when we all know they differ enormously and also their function. It seems, in the end, that everything is a desktop solution for real life actualities.

Having good clothes that are fit for purpose, not apparel that fit policy purposes, should be the goal. They will be used the longest and deliver on DoS. Using ESPR, with PEF as the underpinning logic, will not at all help either the environment, climate change or Europe’s consumers.

So, all in all, listening to the STICA webinar, so well organized by Michael Schragger, gives better insight on where we need to go, than both the JRC organized webinar (which sadly is not publicly available even if it was recorded) and the PEFCR webinar (which can actually be accessed), put together. EU still needs to get their heads around that it’s not at the product level, but at the systems level, that change needs to happen. Let’s hope STICA gave them food for thought.