Author: Rita Dominici

Abstract

This literature review explores the presence and associated health risks of hazardous chemicals in clothing, with a particular focus on dermal exposure. It investigates the potential health effects of skin contact with toxic substances in garments and whether clothing sold from fast fashion brands and luxury brands contain different levels of chemicals. It emerged that chemicals such as aromatic amines, bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and PFAS are commonly found in textiles and have been linked to serious health issues, particularly when skin is exposed to them (Rovira and Domingo, 2019). This review also compares two Greenpeace investigations, one on ultra-fast fashion brand SHEIN and the other on various luxury brands, highlighting that both types of garments can contain harmful substances (Brigden et al., 2014; Cobbing, Wohlgemuth and Panhuber, 2022). It suggests that the issue is widespread across the entire fashion industry. Therefore, stronger regulation, improved transparency, and further scientific research on chemical safety in textiles are needed.

Introduction

Textiles, and therefore clothing, are an essential part of our daily lives, and the processes involved in transforming raw fibers into finished garments are complex and chemically intensive (Avagyan et al, 2015). Whether derived from natural sources such as cotton or wool, or synthetically produced in factories, textile materials go through numerous stages of treatment and finishing that rely on a wide variety of chemical substances (Fransson and Molander, 2012). On one hand, pesticides, fungicides and biocides are used in the cultivation process of natural fibers, on the other hand, chemicals such as dyes, flame retardants, plasticizers, antibacterial agents, antistatic agents and antioxidants are employed in the production of synthetic fibers (Avagyan et al, 2015; Chen et al., 2022) These and other additives are introduced during the different phases of the manufacturing process such as spinning, dyeing, printing and finishing, with the aim to enhance the performance of these textiles for specific uses (Chen et al., 2022). While these substances provide better functionality, appearance, and durability of fabrics, such as wrinkle resistance or water repellency, they also raise serious concerns for both environmental sustainability and public health (Avagyan et al, 2015).

The widespread use of hazardous chemicals in textile manufacturing has long been recognized as a significant source of pollution, with dyes being among the most common contaminants found in textile wastewater (Rovira and Domingo, 2019). Yet, the risks lie even beyond the production phase. Although much of the existing scientific literature has focused on occupational exposure during manufacturing, growing attention is being paid to the risks faced by final consumers, particularly through dermal exposure. Hence, many textiles retain residues of harmful substances that can be released during regular wear, posing risks through direct skin contact, inhalation of microfibers, or even indirect ingestion (Rovira and Domingo, 2019). While certain forms of human exposure to toxins, such as ingestion or inhalation, are the most studied, potential risks linked to skin contact with chemically treated clothes have received less attention.

This literature review aims to examine current scientific knowledge on the presence and health effects of toxic chemicals in clothing. Therefore, the two research questions are: “What are the potential health risks associated with dermal exposure to toxic chemicals present in clothing?” and “Are garments sold by luxury brands safer than those sold by fast fashion brands in terms of hazardous chemicals?”

Method and material

The 22 studies cited in the article were identified using Google Scholar as the main search engine, as well as consulting the reference list of the selected articles to further deepen my research. The search process included a range of keywords related to both the social and chemical dimensions of clothing and textiles, including “chemicals in clothes”, “hazardous chemicals in clothes”, “toxins in fast fashion”, “chemicals in luxury” and “clothes dermal exposure”. The studies vary significantly in scope, with some rooted in chemical analysis while others focus on absorption of hazardous chemicals through the contact of clothes with the skin. These studies often rely on laboratory methods to analyze how specific substances behave when in contact with human skin. The second part of this review aims to examine the presence of hazardous chemicals in garments produced through specific supply chains, a research topic that appears to be less developed. For this reason, only two such studies were included in the article. Both were conducted by Greenpeace and involved testing the chemical content of clothing items. One focused on garments sold by ultra-fast fashion brands, particularly SHEIN, while the other examined clothing items from various luxury brands. Nevertheless, their inclusion provides an insight into a relatively underexplored but important aspect of the issue, trying not only to understand the consequences of exposure to these substances through garments, but also to investigate whether there are differences in the types and levels of chemicals found in items sold by ultra-fast fashion brands such as SHEIN compared to those in designer clothing from luxury labels.

Chemicals in clothes: health risks from skin

The textile industry relies heavily on a wide range of chemical treatments to enhance fabric quality, improve durability, and achieve specific aesthetic effects. Even if many of these chemicals are washed out before the clothes reach stores, not all of them disappear, thus, some residues remain in the fabric and can be released when we wear the clothes, especially when they come into direct contact with our skin (Rovira and Domingo, 2019).

Among the various toxic pollutants found in textiles, particular emphasis is on aromatic amines (AAs). These substances can be released under certain conditions from azo dyes: a widely used class of synthetic dyes in the textile industry (Brigden et al., 2014). As summarized by Platzek (2010), exposure to aromatic amines through consumer products can lead to serious health risks, primarily due to the mutagenic and/or carcinogenic nature of certain AAs. The harmful effects of these chemicals are closely linked to producing certain substances capable of causing damage to DNA and proteins (Brüschweiler and Merlot, 2017). In response, countries including EU member states and China have implemented regulations banning the sale of textiles that may release carcinogenic amines above certain thresholds when in contact with the skin. EU regulations currently restrict 22 specific amines with a maximum limit of 30 mg/kg (EU, 2002), while Chinese regulations are even stricter, setting a limit of 20 mg/kg and including two additional compounds (Bridgen et al., 2014).

Beyond azo dyes, there are other chemicals found in textiles that raise serious health concerns. These include Bisphenol A (BPA), which is another particularly concerning compound. Commonly discussed in the context of plastics, BPA is also present in textiles, especially those with printed designs or made from synthetic fibers (Herrero et al., 2023). BPA can be introduced during textile production both as a component of dyes and antioxidants and as an additive in polyester to improve colorfastness, antistatic properties, and moisture control (Xue et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019; Undas et al., 2023, as cited in Herrero et al., 2023). Its presence in clothing can become hazardous with prolonged contact with the skin, which increases the risk of dermal absorption -particularly for sensitive populations such as pregnant women and children (Herrero et al., 2023). Exposure to BPA has been associated with a variety of adverse health outcomes. In children, both prenatal and postnatal exposure has been linked to behavioral disorders, asthma, obesity, immune system dysfunctions, hormonal disturbances, and altered pubertal development (Herrero et al., 2023). In adults, elevated BPA levels have been connected to breast and prostate cancer, metabolic disorders, and diabetes (Chen et al., 2016; Freire et al., 2019). Furthermore, BPA analogs like bisphenol S (BPS) and bisphenol F (BPF) may have endocrine-disrupting effects that are equal to or even greater than those of BPA itself (Herrero et al., 2023).

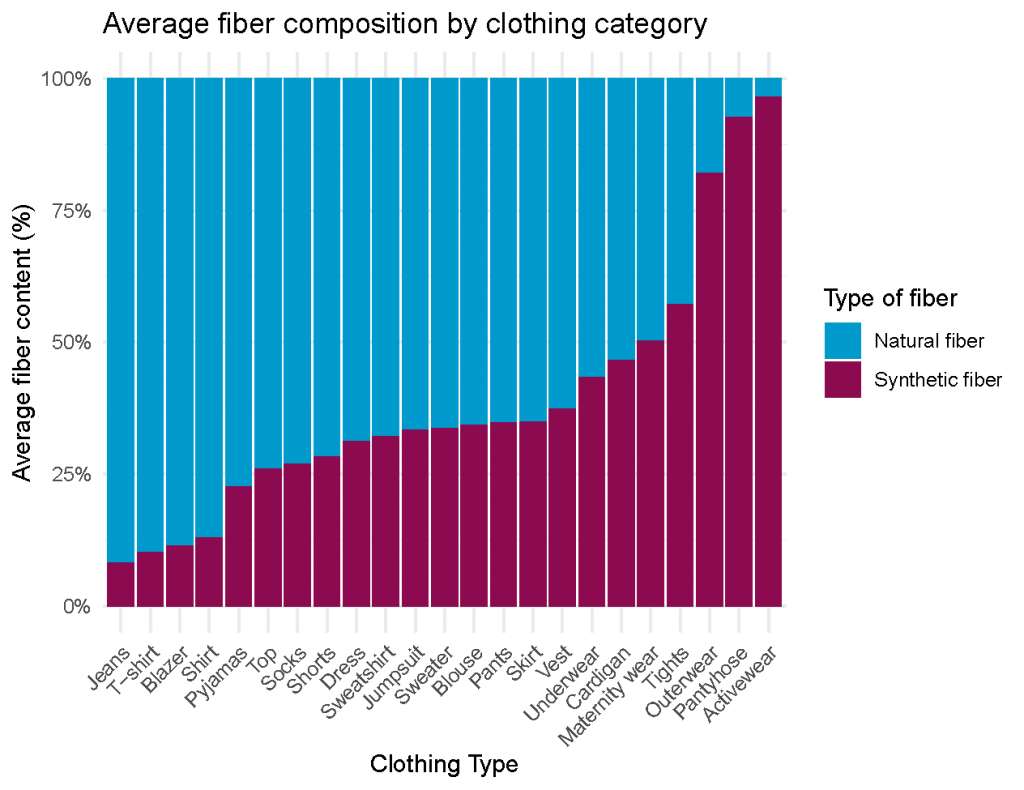

Other chemicals used on clothing that can cause harm are phthalates: chemicals used to soften plastics and often found in printed clothes. For this reason, it is important to consider that the final consumers of textiles containing printed PVC are often children, who are a group particularly vulnerable to endocrine-disrupting compounds due to their stage of development (Martínez et al., 2018). The review by Caldwell (2012) adds to these concerns by highlighting new findings on these substances, including their potential to cause chromosomal damage, accelerate cancer progression, and alter gene expression, even at lower concentrations. PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), APEOs (alkylphenol polyethoxylates), and NPEs are other chemicals commonly used during the production process with the aim of enhancing softness, smoothness, and water resistance (Chen et al., 2022). However, PFAS have become a major environmental concern due to their persistence and low degradability. Substances like PFOS (Perfluorooctanesulfonate) and PFOA, have been linked to serious health risks, including effects on fertility, hormonal disruption, and childhood obesity. PFAS concentrations have been found in various textiles regardless of fiber type, with higher levels observed in polyester than in nylon (Chen et al., 2022). Formaldehyde is another chemical of concern in the textile industry. Traditionally used to improve anti-creasing properties, compounds that release formaldehyde have been associated with eye, nose, and throat irritation, allergic skin reactions, and even cancer, as classified by the IARC (Group 1) (Cobbing, Wohlgemuth and Panhuber, 2022). Although modern finishing techniques release lower amounts of formaldehyde, elevated levels have still been found in certain garments (Rovira and Domingo, 2019).

Beyond the chemicals briefly discussed, a wide range of other hazardous chemicals are also present in textile products. These include heavy metals such as lead and cadmium, nickel (a known allergen), and flame retardants, all of which can be absorbed through skin contact. These substances can contribute to systemic health risks and should not be overlooked in risk assessments concerning dermal exposure to garments.

Finally, after this brief overview of some of the chemicals used in clothing production and the effects of their contact with the skin, the following paragraphs will explore in more depth the relationship between the use of these additives and the production of ultra-fast fashion and luxury brand garments.

Chemical usage in clothes: ultra-fast fashion vs. luxury brands

The fast fashion industry has long been criticized for its high-volume, high-speed production cycles, and for the harsh environmental and social consequences produced by its business model. However, the phenomenon of ultra-fast-fashion brands has appeared in recent years (Cobbing, Wohlgemuth and Panhuber, 2022). This model goes beyond fast-fashion production in speed and scale, with suppliers expected to deliver goods within just 3 to 7 days, which are then shipped directly to global consumers via air shipment. Such logistics are environmentally damaging and linked to violations of labor and regulatory frameworks (Cobbing, Wohlgemuth and Panhuber, 2022).

To investigate the risks linked to this model of production and the use of chemicals in the clothes, Greenpeace conducted a chemical analysis of 47 garments purchased from SHEIN platforms in Austria, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Switzerland, as well as from a temporary store in Munich. The tests, carried out by an independent laboratory, revealed alarming levels of hazardous chemicals, ignoring EU safety regulations and raising serious concerns about the companies’ violations of consumer safety and environmental regulations (Cobbing, Wohlgemuth and Panhuber, 2022).

The garments were tested for a broad spectrum of toxic substances, including formaldehyde, phthalates, heavy metals, PFAS, and aromatic amines from azo dyes. The results confirmed that several items contained illegal levels of harmful chemicals, posing potential threats to workers in the supply chain and communities living near manufacturing sites, where these pollutants may be discharged into the air and water, and final consumers, through indirect digestion, inhalation and skin contact (Cobbing, Wohlgemuth and Panhuber, 2022).

This issue is not limited to Europe. In Canada, an independent investigation found that 1 in 5 items of clothing from three fast fashion retailers, Zaful, AliExpress, and SHEIN, contained high levels of toxic chemicals. The latter’s garments contained dangerous levels of substances such as lead, PFAS, and phthalates (CBC, 2021). In one shocking case, a toddler’s jacket sold by SHEIN contained lead levels 20 times higher than Canada’s legal limit. The Swedish Chemicals Agency (2013) has also warned of the increased risk associated with purchasing goods from non-EU-based online vendors, noting the difficulty in monitoring chemical compliance when companies operate without physical presence within the EU (KEMI, 2016). Efforts such as the EU Safety Gate system and the voluntary Product Safety Pledge+ aim to improve accountability among online marketplaces. Major platforms like Amazon have signed on, but SHEIN remains absent from these initiatives, raising further concerns about its commitment to consumer safety (European Union, 2023).

It was only in 2023 that SHEIN made public its Restricted Substances List (RSL) and Manufacturing Restricted Substances List (MRSL), -documents that outline hazardous chemicals and the regulatory limits that must be followed both within the EU and internationally. Despite these improvements, full transparency has not yet been achieved. For example, the company still does not publish a suppliers list, which would need to include its wet processing suppliers, where hazardous chemicals are most intensively used, even though such a list appears to exist, (Cobbing, Wohlgemuth and Panhuber, 2022).

A similar investigation was conducted, this time focusing on garments produced by luxury brands. Bridgen, Hetherington, Wang, Santillo and Johnston (2014) analyzed 27 luxury clothing and footwear items from major brands such as Dior, Dolce&Gabbana, Armani, Hermès, Louis Vuitton, Marc Jacobs, Trussardi, and Versace. These products were purchased in nine different countries or regions between May and June 2013 and were reportedly manufactured in at least seven different countries, although the country of origin for five items could not be identified. The chemical screening focused on a range of hazardous substances, including nonylphenol ethoxylates, carcinogenic amines released under reducing conditions, phthalates, organotins, per- and polyfluorinated chemicals, and antimony.

Findings confirm the presence of multiple hazardous substances in luxury textile and footwear products, either as manufacturing residues or intentionally added components. Among these, nonylphenol ethoxylates (NPEs) were the most frequently detected, found in items from five of the eight brands tested and in seven of the nine regions where products were purchased. NPEs were also present in garments made in three out of seven identified manufacturing countries, suggesting their continued use across global luxury supply chains. The detection of NPEs in finished products indicates their use during production, with potential environmental impacts both at the manufacturing stage and during consumer use-especially through washing (Bridgen et al., 2012). Moreover, phthalates were also found in all five items with plastisol-printed fabrics, though in lower concentrations (Brigden et al., 2014). No carcinogenic amines or organotins were detected in the tested samples, though previous research has identified these substances in textiles, highlighting ongoing concerns about product safety.

To conclude, although there is a common perception that SHEIN stands out as particularly harmful within the fashion industry, especially in terms of hazardous chemical use and environmental impact, it is difficult to find systematic studies that directly compare SHEIN to other online platforms, brands, or business models. The two main studies reviewed, one focusing on luxury brands (Brigden et al., 2014) and the other on SHEIN (Cobbing et al., 2024), analyze many of the same groups of hazardous substances, including phthalates, NPEs, formaldehyde, PFAS, and heavy metals. However, while the results are comparable in terms of the chemical classes investigated, differences in sample type and analytical approach limit the possibility of making direct comparisons and therefore drawing conclusions. Moreover, it is important to underline that neither study clearly defines the specific laboratory methods used for the chemical analyses, making it difficult to assess consistency or comparability. In addition, the studies were conducted a decade apart, within different regulatory frameworks and market conditions, which further complicates any attempt at comparison. Finally, it is important to remember that even if these studies include multiple samples from each brand, the number of items analyzed remains small relative to the vast product range offered by these companies. Therefore, although these two studies are not directly comparable due to the reasons defined above, a broad comparison still offers a valuable perspective on the presence of hazardous chemicals in the textile industry which affects both ultra-fast fashion and luxury brand production. The latter phenomenon, in particular, will be further explored in the following section.

To the core of the supply chain

The detection of harmful chemicals in both ultra-fast fashion and luxury clothing shows that this problem affects the entire fashion industry. To address it properly, it is important to have a better understanding of how global textile supply chains work and why they are so complex. While institutions, like the European Union, have established strict controls on numerous hazardous substances, enforcing such standards across the entire textile supply chain is a major challenge. This difficulty stems from the globalization of production, with many manufacturing processes relocated to countries where environmental regulations and labor protections are weaker. Hence, the complex supply chains, which are characterized by a multitude of suppliers and subcontractors, further complicate efforts to monitor chemical use effectively. Adding to this complexity is the rapid turnover of fashion trends, which frequently alters the types of prints, dyes, and chemical treatments employed in textile production (Fransson & Molander, 2013).

Börjeson, Gilek and Karlsson (2014) outline four key points that explain the complicated situation involving clothing production and the use of toxic chemicals. First, public and private textile producers hardly own production facilities; instead, they depend on distributed suppliers and subcontractors, often selected for their lower labor costs in developing countries (Müller et al., 2009; Ciliberti et al., 2008). Second, the environmental and health impacts of chemicals used in textile production are significant, with risks related to different fibers and stages: from pesticide use in natural fiber cultivation to dyeing processes to chemical treatments like flame retardants and water repellents (Assmuth et al., 2011). Third, regulatory frameworks vary widely across different countries. While textile-importing regions like the EU have advanced chemical legislation (e.g., REACH), producer countries often maintain more lenient regulations and weaker enforcement (Eriksson et al., 2010). Fourth, since fashion is moving so fast, dyes and other chemicals are frequently changed without proper estimation of their long-term impacts, making it difficult to develop proper regulations.

Although many scholars view supply chains as single, integrated entities, the empirical evidence from the study by Börjeson, Gilek and Karlsson (2014) suggests that this perspective does not fully apply to textile supply chains. To move toward more responsible supply chain practices, a shift is needed toward enhancing commitment and knowledge management., in order to achieve better integration across the complex global networks and interactions that characterize textile supply chains (Börjeson, Gilek and Karlsson, 2014).

Conclusions

The reviewed literature provides evidence that the use of hazardous chemicals in textile production poses significant health and environmental risks and tries to understand whether there is a difference in terms of chemical safety between garments sold by ultra-fast-fashion brands and luxury brands. Despite the aesthetic and functional purposes that these substances have, such as color fastness, durability, and water repellency, their presence in the manufacturing stage and in the final products brings serious concern. From the very first parts of production to the final finishing processes of garments manufacturing, chemicals such as aromatic amines, bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and nonylphenol ethoxylates (NPEs) persist throughout the supply chain (Avagyan et al, 2015; Rovira and Domingo, 2019). These substances have been shown to be mutagenic, carcinogenic, endocrine-disrupting, and otherwise harmful to human health through dermal exposure. Nevertheless, dermal absorption as a way of exposure has been underexplored in comparison to dietary and inhalational pathways, despite growing evidence that chemicals in clothing can be absorbed through the skin and enter systemic circulation, posing risks for consumer and especially more vulnerable population groups such as children and pregnant women (Rovira and Domingo, 2019).

From the literature analyzed, it is difficult to ascertain whether one supply chain is safer than the other, as the current evidence does not allow for such a conclusion. To make reliable and objective comparisons, it would be necessary to apply identical chemical testing and sampling methods with the specific aim of evaluating garments under the same conditions. Nevertheless, the existing research provides valuable insight into the situation across both fast fashion and luxury clothing, highlighting the systemic nature of the problem and the widespread use of hazardous chemicals throughout the textile industry. It is not simply a matter of brand reputation or price point; it reflects a broader failure of the global supply chain of the clothing industry to prioritize health and environmental safety across its production (Cobbing, Wohlgemuth and Panhuber, 2022; Brigden et al., 2014). Countries and institutions such as the European Union have strict regulations on hazardous chemicals but forcing them across global textile supply chains remains a major challenge. Much production is outsourced to countries with weaker environmental and labor protections, while complex and fragmented networks of suppliers and rapid fashion cycles further complicate chemical monitoring (Börjeson, Gilek and Karlsson, 2014).

Future research

In the future, a more integrated and straightforward international framework is needed to protect both consumers and workers. This includes mandatory chemical disclosure, stricter testing and certification requirements, and stronger enforcement mechanisms, especially including the online marketplaces. In order to achieve this goal, given the wide variety of chemical substances potentially present in textile products and the rarity of systematic product controls, expanding laboratory-based research on the effects of these numerous agents is crucial. Such research should contribute to the establishment of clear and universal regulations that can serve as reference points during inspections and regulatory enforcement. This would help preserve consumer health and ensure greater accountability throughout the supply chain. Following this logic, future research could dig deeper into this field to better understand whether there are differences in dermal exposure to chemicals via garments between different social groups, divided by gender, age and occupation and try to understand if some long-term effects can be identifiable. At the same time, studies could investigate how different fabric types — such as natural versus synthetic fibers — affect the release and dermal absorption of hazardous substances. As stated before, expanding scientific research on this topic would support the improvement of existing regulations, with the goal of protecting both the health of producers, who work closely with these substances, and consumers who wear clothing daily.

References

Assmuth, T., Häkkinen, P., Heiskanen, J., Kautto, P., Lindh, P., Mattila, T., Mehtonen, J., & Saarinen, K. (2011). Risk management and governance of chemicals in articles: Case study textiles (Vol. 16). Finnish Environment Institute.

Avagyan, R., Luongo, G., Thorsén, G., & Östman, C. (2015). Benzothiazole, benzotriazole, and their derivates in clothing textiles—a potential source of environmental pollutants and human exposure. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 22(8), 5842–5849.

Börjeson, N., Gilek, M., & Karlsson, M. (2015). Knowledge challenges for responsible supply chain management of chemicals in textiles–as experienced by procuring organisations. Journal of Cleaner Production, 107, 130–136.

Brigden, K., Santillo, D., & Johnston, P. (2012). Nonylphenol ethoxylates (NPEs) in textile products, and their release through laundering (Greenpeace Research Laboratories Technical Report 01/2012). http://www.greenpeace.to/greenpeace/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Dirty_Laundry_ProductTesting_Technical_Report_01-2012.pdf

Brigden, K., Hetherington, S., Wang, M., Santillo, D., & Johnston, P. (2014). Hazardous chemicals in branded luxury textile products on sale during 2013 (Greenpeace Research Laboratories Technical Report No. 1).

Brüschweiler, B. J., & Merlot, C. (2017). Azo dyes in clothing textiles can be cleaved into a series of mutagenic aromatic amines which are not regulated yet. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 88, 214–226.

Caldwell, J. C. (2012). DEHP: Genotoxicity and potential carcinogenic mechanisms—A review. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research, 751(2), 82-157.

CBC. (2021, October 1). Experts warn of high levels of chemicals in clothes by some fast-fashion retailers. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/marketplace-fast-fashion-chemicals-1.6193385

Chen, D., Kannan, K., Tan, H. L., Zheng, Z. G., Feng, Y. L., Wu, Y., & Widelka, M. (2016). Bisphenol analogues other than BPA: Environmental occurrence, human exposure, and toxicity—a review. Environmental Science & Technology, 50(11), 5438–5453.

Chen, Y., Chen, Q., Zhang, Q., Zuo, C., & Shi, H. (2022). An overview of chemical additives on (micro) plastic fibers: Occurrence, release, and health risks. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 260(1), 1–22.

Ciliberti, F., Pontrandolfo, P., & Scozzi, B. (2008). Investigating corporate social responsibility in supply chains: A SME perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(15), 1579–1588.

Cobbing, M., Wohlgemuth, V., & Panhuber, L. (2022). Taking the shine off Shein: A business model based on hazardous chemicals and environmental destruction. Greenpeace Germany.

Eriksson, J., Gilek, M., & Rudén, C. (2010). Regulating chemical risks: Multidisciplinary perspectives on European and global challenges. Springer.

European Union. (2002). Directive 2002/61/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 July 2002. Official Journal of the European Communities, L243, 15–18.

European Union. (2023). Safety Gate: The EU rapid alert system for dangerous non-food products.

Fransson, K., & Molander, S. (2013). Handling chemical risk information in international textile supply chains. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 56(3), 345–361.

Freire, C., Molina-Molina, J. M., Iribarne-Durán, L. M., Jiménez-Díaz, I., Vela-Soria, F., Mustieles, V., Arrebola, J. P., Fernández, M. F., Artacho-Cordón, F., & Olea, N. (2019). Concentrations of bisphenol A and parabens in socks for infants and young children in Spain and their hormone-like activities. Environment International, 127, 592–600.

Herrero, M., Souza, M. C. O., González, N., Marquès, M., Barbosa, F., Domingo, J. L., Nadal, M., & Rovira, J. (2023). Dermal exposure to bisphenols in pregnant women’s and baby clothes: Risk characterization. Science of The Total Environment, 878, 163122.

KEMI. (2016). Increased e-commerce – increased chemicals risks? Swedish Chemicals Agency.

Martínez, M. A., Rovira, J., Prasad Sharma, R., Nadal, M., Schuhmacher, M., & Kumar, V. (2018). Comparing dietary and non-dietary source contribution of BPA and DEHP to prenatal exposure: A Catalonia (Spain) case study. Environmental Research, 166, 25–34.

Müller, M., Gomes dos Santos, V., & Seuring, S.(2009). The contribution of environmental and social standards towards ensuring legitimacy in supply chain governance. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(4), 509–523.

Platzek, T. (2010). Risk from exposure to arylamines from consumer products and hair dyes. Frontiers in Bioscience (Elite Edition), 2, 1169–1183.

Rovira, J., & Domingo, J. L. (2019). Human health risks due to exposure to inorganic and organic chemicals from textiles: A review. Environmental Research, 168, 62–69.

Swedish Chemicals Agency. (2013). Hazardous chemicals in textiles: Report of a government assignment.