Volumetric wardrobe studies to quantify the current clothing stock and wardrobe composition with adults in Flanders (Belgium).

Authors: Veerle Vermeyen (PhD student, KU Leuven), Filip Germeys (Professor, KU Leuven)

Today, conversations about sustainable fashion often focus on buying better and consuming less—yet we still know remarkably little about what people actually keep in their wardrobes. This gap in knowledge limits our ability to design effective interventions and evaluate progress toward a more circular fashion system. To develop meaningful strategies, we need a better understanding of the “use phase”: how many garments people own, how they use them, and how these patterns differ across the population.

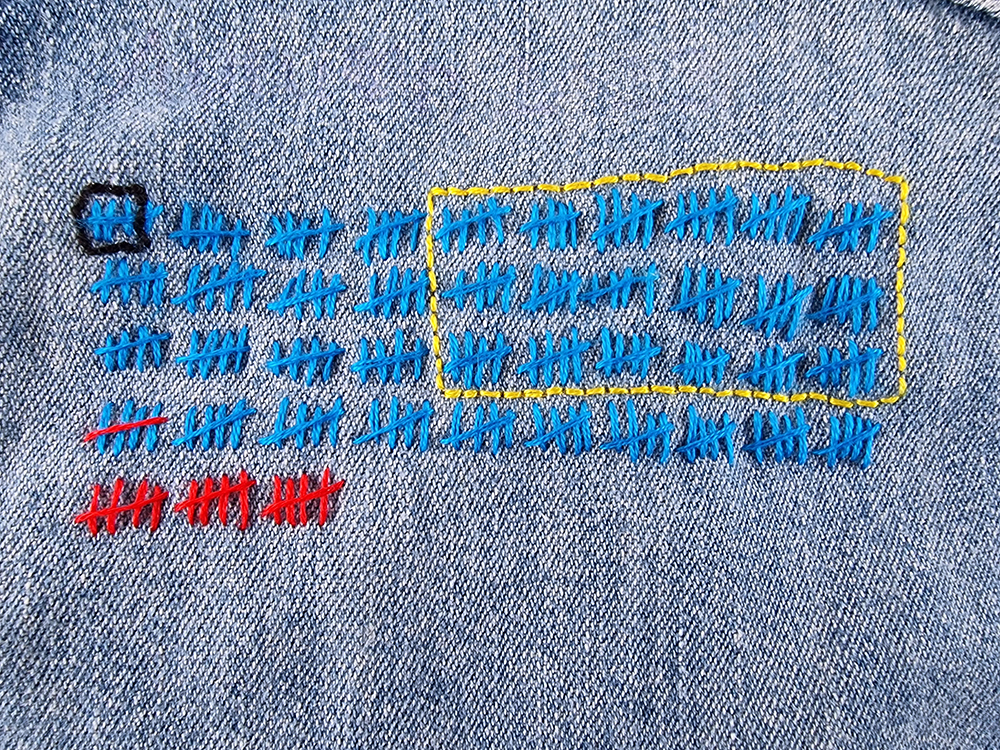

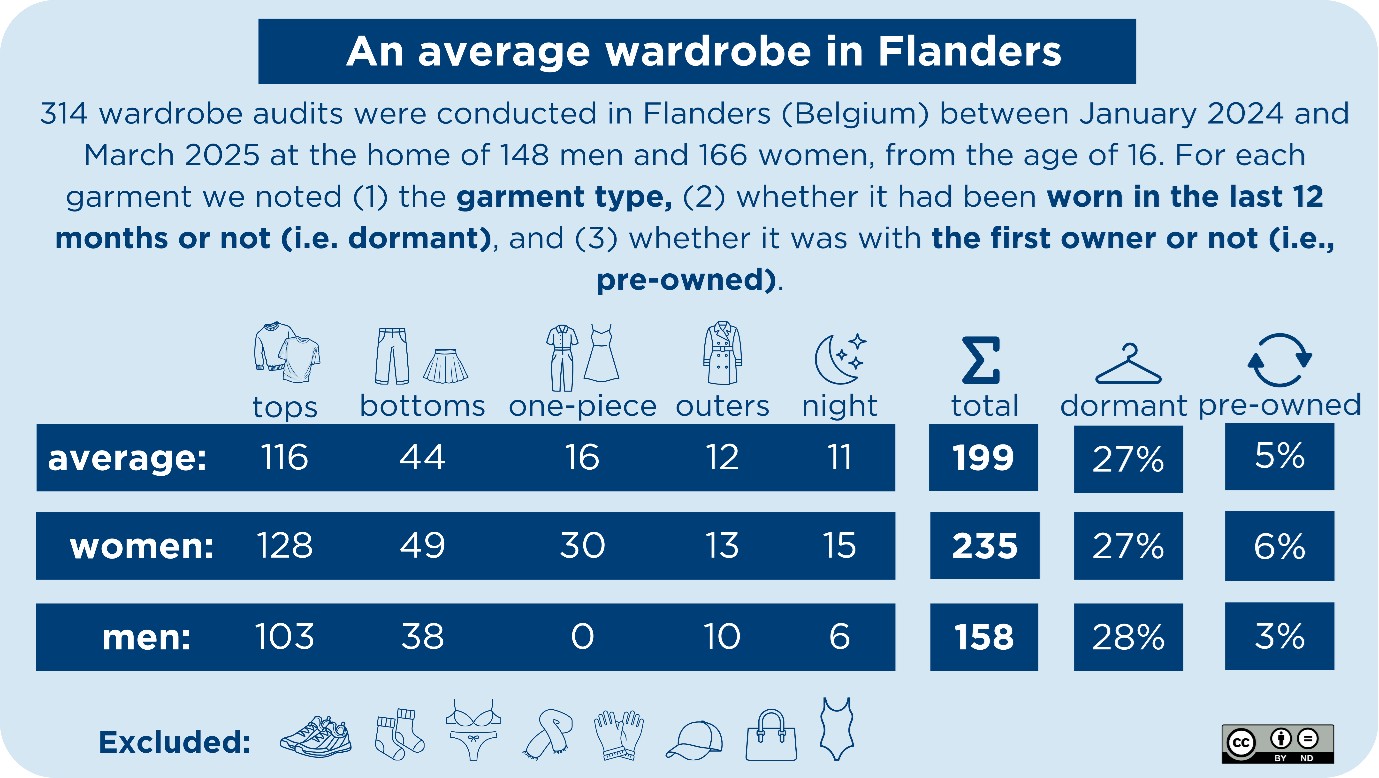

With this in mind, my research set out to map the current clothing stock and wardrobe composition among adults in Flanders (Belgium). We were particularly interested in examining how wardrobe size and content vary between individuals, providing a baseline that helps illuminate the diversity of wardrobe practices within society. We conducted a volumetric wardrobe study consisting of a quantitative audit of all the garments within the study scope at participants’ home. For each item, we recorded three attributes: (1) the garment category, (2) whether the participant was the first owner of the item or not (“first-owner” vs “pre-owned”), and (3) whether the garment had been worn in the prior 12 months (“active” vs “dormant”). Underwear, footwear, and accessories were not included in the audit.

Methodology

Potential participants were initially identified through an online survey. To ensure diversity, the pool was stratified by age and gender, after which individuals were selected using convenience sampling. For example, as the wardrobe audits happened at participants’ homes, participants were selected so that researchers could reach multiple participants within the same day. In total, 314 participants took part in the research: 47% male and 53% female, from the age of 16. All participants lived either in Flanders, the northern region of Belgium, or in the Brussels Capital Region.

The wardrobe audits were carried out in two rounds using a consistent protocol. In the first round, five researchers conducted audits between January and March 2024 as part of their master’s thesis projects. A second team of five researchers repeated the same procedure between January and March 2025, allowing us to expand the dataset while maintaining methodological consistency.

After each audit, researchers posed a set of follow-up questions. In the first round, these focused on dormant garments and explored why participants continued to keep items they had not worn in the past year. In the second round, the questions shifted toward understanding garment service lifetimes and assessing the potential for reducing overall wardrobe volume.

Results

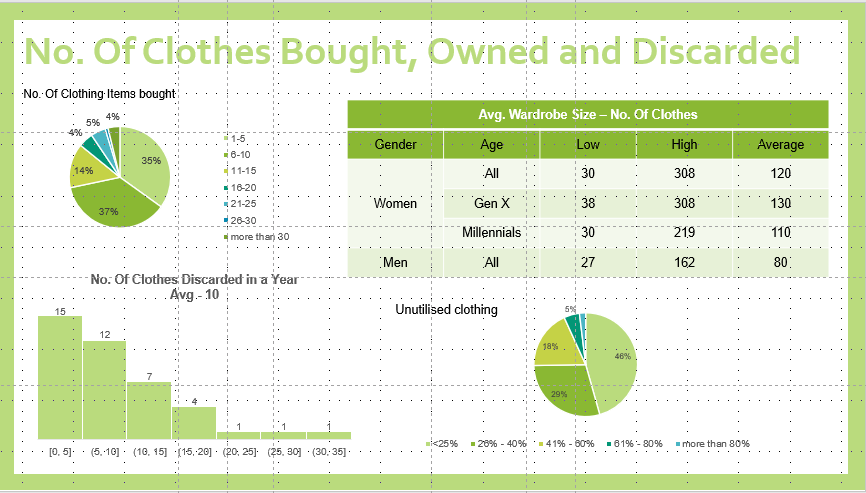

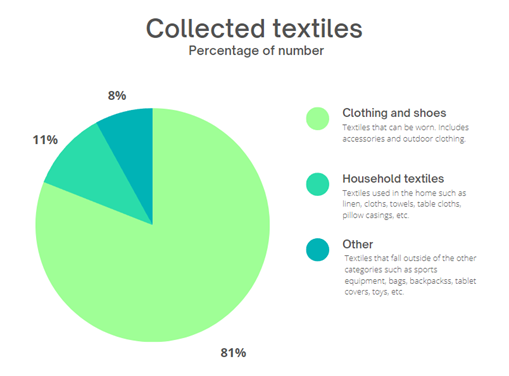

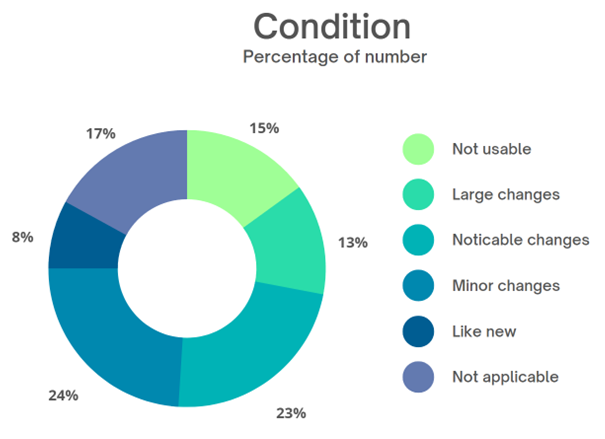

The main results of the wardrobe audits are summarised in the figure below, putting initial numbers to an area where assumptions are often made. The research provides a baseline for understanding the current stock and use of clothing in Flanders (Belgium). The 314 wardrobe audits have since been published in an online database, and the findings of the first data collection round are published as a research article in the Journal of Circular Economy.

The baseline data on wardrobe size and composition will serve as the reference for future case studies focusing on specific demographic or behavioural groups. This research will rely more on qualitative methods to gain deeper insights into the underlying dynamics of current consumption patterns. By doing so, we aim to better understand the motivations, behaviours, and trends driving clothing usage in Flanders and inform strategies for more sustainable consumption.

This research builds upon previous volumetric wardrobe studies, such as by Maldini et al. (2017) in the Netherlands. Further studies could be conducted in regions with different climatic, cultural, or economic profiles to Flanders to ascertain differences. Conducting in-person wardrobe audits offers a true ‘behind-the-scenes’ view of how people manage, store, and think about their clothing. You notice nuances that would never surface through online surveys — patterns, habits, contradictions, and surprises that spark new questions and inspire new lines of research.

Reference

Maldini, I., Duncker, L., Bregman, L., Piltz, G., Duscha, L., Cunningham, G., Vooges, M., Grevinga, T., Tap, R., & van Balgooi, F. (2017). Measuring the Dutch clothing mountain: data for sustainability-oriented studies and actions in the apparel sector. PublishingLab.

Further references

Dataset with wardrobe audits:

Vermeyen, Veerle; Van Acker, Karel; Germeys, Filip, 2025, “Size and Composition of Wardrobes in Flanders”, https://doi.org/10.48804/EQBNMJ, KU Leuven RDR, V1

Published results of the first round:

Vermeyen, V., Alaerts, L., Worrell, E., Van Acker, K., & Germeys, F. (2024). Behind Closed Doors: Examining the Stock of Clothing in Individuals’ Wardrobes. Journal of Circular Economy, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.55845/OQEE5977

Pilot study on wardrobe reduction:

Vermeyen, V., Duyvejonck, M., & Germeys, F. (2025). From excess to essential: Exploring the Potential of Adopting Smaller Wardrobes. Proceedings of the 6th Product Lifetimes and the Environment Conference (PLATE2025), (6). https://doi.org/10.54337/plate2025-10360