New PhD makes a splash: The function of the laundry and the limitation in self-reported data

Chalmers University In the heart of Gothenburg hosted the defense for Erik Klint on September 6th. Klint’s PhD, consisting of 5 published articles and some additional published material, was discussed with professional curiosity and benevolence, and the atmosphere was positive throughout.

Author: Ingun Grimstad Klepp

It is not easy to work interdisciplinary, but as the head of the Grading committee Professor Michael Zwicky Hauschild, Denmark’s Technical University summed up: Here we have well-defined research questions, identified knowledge gaps and an exciting journey between the two different academic traditions, a travel from environmental impact to psychology and then back again to Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs).

Functional unit must define a function

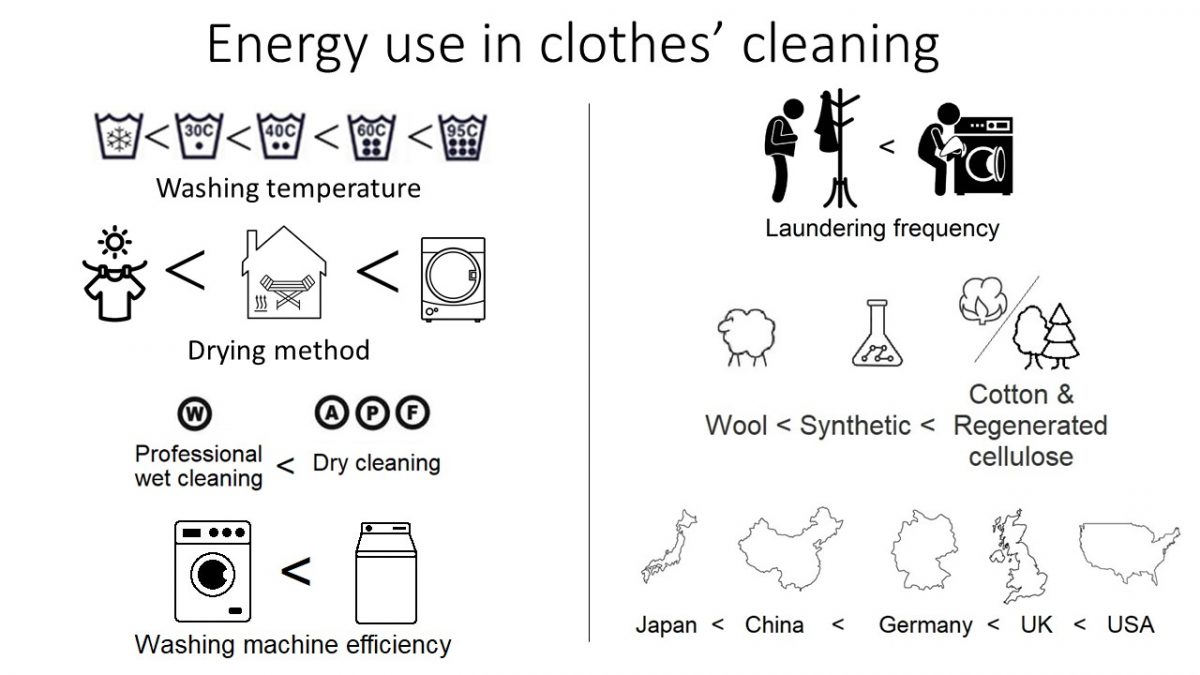

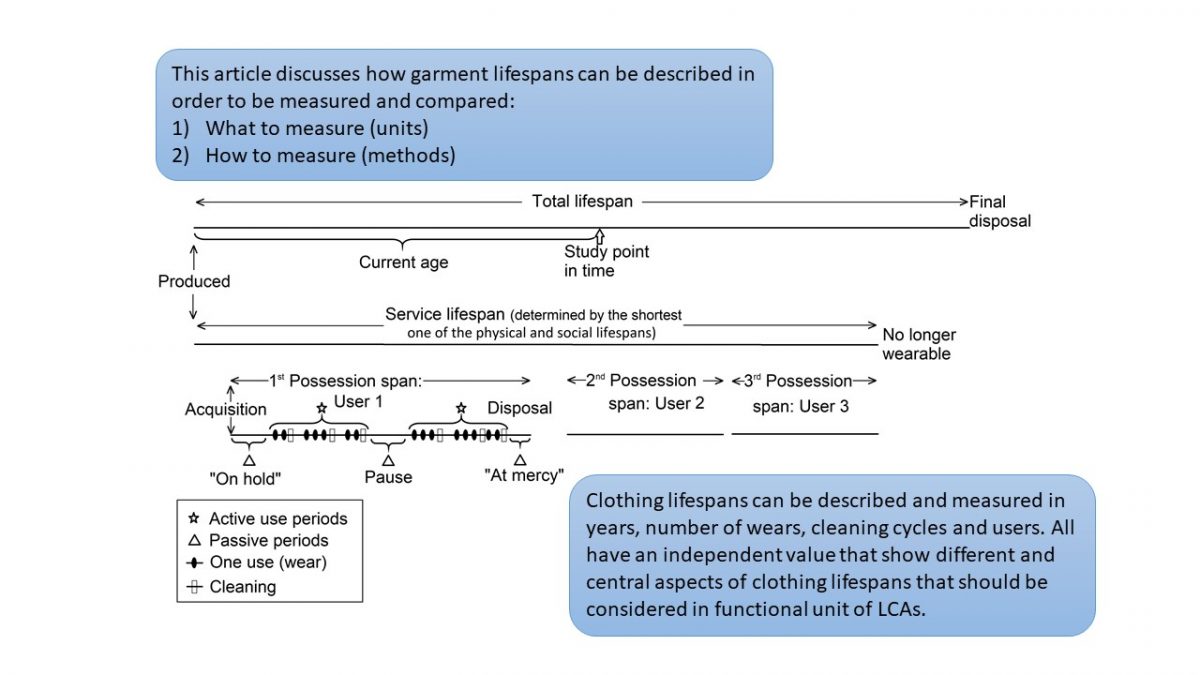

The work’s most important conclusion is that what people do – and what psychologists call behavior – must be included in LCAs. The functional unit cannot be kilos of laundry, but rather what the function is or can be. The most important function of clean clothes is to make us feel socially safe. This is the functional unit that Klint argues for and was supported by the LCA expert from the Technical University of Denmark. A FU must be a function, something the product or test is used for in order to achieve an outcome.

There was a lot of discussion about this point during the defense, both from the opponent, Professor Wencke Gwozdz, Justus Liebig University of Giessen, and from the audience. Because: Doesn’t laundry also have other functions? And can this be a function or functions that is or are actually difficult to measure? Yes, but as Klint demonstrates, it is this (that is, what is needed to perceive something as clean) that has changed the most and also has the greatest impact on the environmental footprint of laundering.

Both during the discussion and in the thesis, Klint draws in clothes and their functions, and I took the opportunity to point out that the use of LCAs is much more problematic for clothing than for laundry, and that his work will thus possibly have greater consequences for this field.

Better data

After the defense, the supervisors and the committee took part in a tour of the Living Lab, flats inside the Chalmers campus area that has been trialing new solutions and more community-based services. A shared laundry room was located centrally in the building by the entrance, and together with a pleasant living room that included tools for repairing clothes, exercising, or a space just for hanging out. The Living Lab has student housing and apartments, and those who live there must approve that data from their laundering is included in research.

Supervisor Gregory Peters Professor, Environmental Systems Analysis, Technology Management and Economics, proudly showed off how they had modified the machines to collect data and also the chips they had sewn into the clothes to collect details about washing frequency – among other things. In his work, Klint contrasts what people say and what they do. And the difference is big! Not least, this applies to washing “full machines”, where the result shows that that what people think is a full machine, varies greatly. This has major consequences for the environmental impact of laundry, which easily becomes more than twice as high if the filling rate drops to half capacity. In the comparison of self-reported data and data from the Living Lab, Klint also used pictures to illustrate what the machine looked like when it was fully loaded. This gave a clear picture closer to the actual degree of filling, than words alone.

Numbers and culture

The work done by Klint is based on quantitative analyzes and a lot of number crunching – as is expected in a thesis that seeks to improve an LCA tool. But Klint himself found that the cultural aspects of cleanliness and changes in these, alongside that there are so many different ways of thinking about how things should be sorted and what can be washed together with what, were a very interesting aspect to explore. It was thus with great respect for the nuances of human nature that his analyzes were made. He found that attitudes towards the environment played no role in washing frequency, but that other variables could explain quite a bit. Another nail in the coffin for the idea of ”enlightenment” as important for changing people’s actions.

Increased sensitivity to disgust, shame, or cleanliness norms were associated with a higher washing frequency per person. Thus, most important were shame and disgust – i.e. the discomfort perceived in what dirt and smell causes in social settings.

Both concepts were discussed based on psychological theories and literature on these feelings. Klint argued that people do not load a load of laundry to use (or not use) energy, but to have clean clothes, or because the laundry basket is full. This is obvious – but as long as LCAs are developed with a technical starting point, e.g. how efficient a machine is – it is necessary to point this out and change the LCAs so that what people actually do, is taken into account.

Changes in technology and infrastructure also change habits, and this interaction disappears if only kilograms of laundry are studied, not the need for clean clothes. This then immediately raises bigger questions because what is really a need? And how is it that what is perceived as necessary, common, decent, etc. changes? Klint couldn’t answer everything, and this was not expected. Nevertheless, we couldn’t help ourselves – because his work opens up big questions that will probably become even more urgent if we transfer the discussion from laundry to clothing.

Despite the fact that we at SIFO is neither an LCA expert, nor a strong psychological approach, the conclusions was just as much what we have – or could have – done a lot. The will to find better data than what people themselves report, and not least the combination of technical and social science approaches, made the work familiar in a certain sense. There were also plenty of SIFO references in all the articles.

Cheers for Chalmers

It was fun to take part in this defense, everything from small technical details and information, to the big questions, were handled quickly and professionally. There was a good mix of friendly conviviality and academic celebration over the ceremony.

For me, this was an educational trip that shows that other subjects and traditions have a lot to contribute, but also that ideas and traditions we have advocated for decades, such as the importance of the use phase, are indeed supported in other subjects and methodologies.