We attended the PLATE-conference in Helsinki with 7 papers, you can read more here.

The PLATE conference has over the years brought together very important profiles and institutions that all work with the concept of design for longevity, the use phase of products, systems and processes around products, and this was also the case in Helsinki. The group of scholars in fashion, clothing and textiles has grown considerably, so it felt very much like a ‘family get-together’ where senior scholars catch up with their respective work, and where aspiring junior scholars get to present their new and fresh ideas on the conference topic.

More Critical

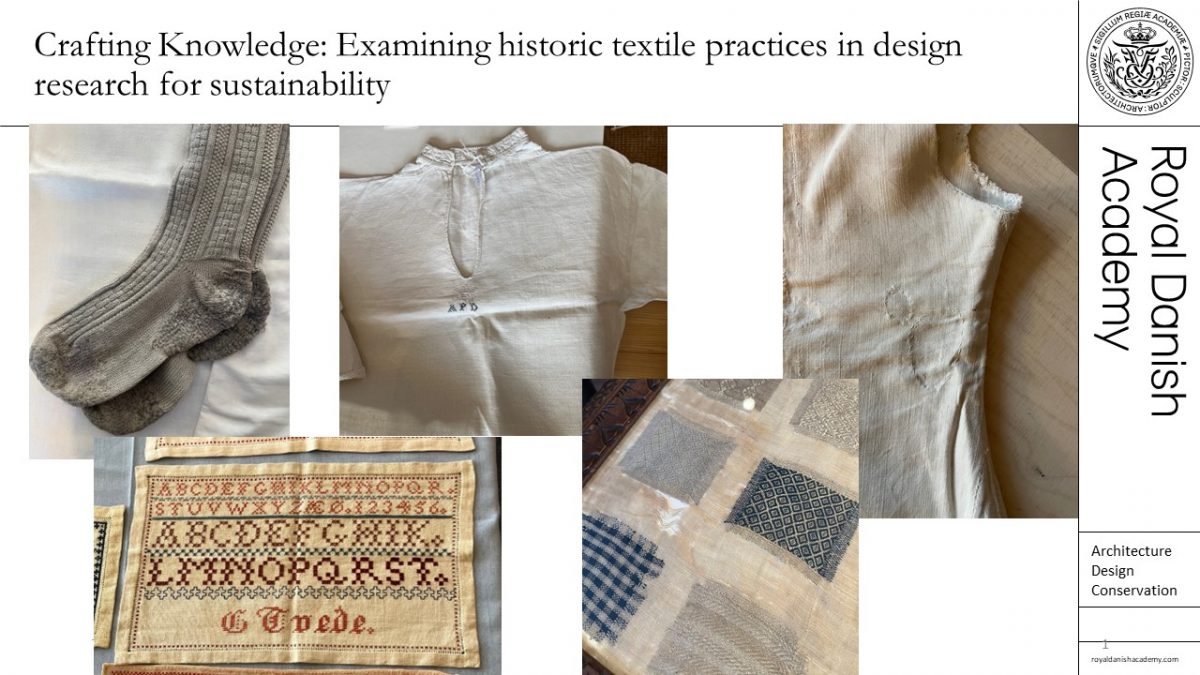

Else Skjold from the Royal Danish Academy of Arts, and one of the work package leaders in CHANGE, has reflected on the more critical and said: “What was evident for this particular conference was how there is a development in the field towards a more systemic approach that involves policy framework, assessment schemes for longevity parameters, such as e.g. the use phase, the building up of ‘eco-systems’ of stakeholders and citizens for better resource efficiency, or educational schemes at particularly design schools.

These kinds of approaches seem to predict the work within the field for the coming years, in the shared understanding that the design of products alone will not affect any change in itself – there needs to be a deeper transformation at both cultural, political, and economic level before long-lasting design can become the new normal.”

Irene Maldini, who is also in CHANGE, agrees with this overall reflection, stating that “the PLATE community is maturing and developing more critical research about product lifetimes. In past editions, research focused mostly on how to apply well-known circular economy strategies. In every edition there are more realistic perspectives about the impact and savings of reuse or repair, critical papers on the impacts of clothing reuse, for instance, were quite common in this edition, and good.”

One of these was “Does Resale Extend the Use Phase of Garments? Exploring Longevity on the Fashion Resale Market”, Presented by Mette Dalgaard Nielsen from The Royal Danish Academy, a paper we look forward to reading and using both in Wasted Textiles and “Se min brukte kjole” projects.

Kerli Kant Hvass, a member of the Wasted Textiles consortium, adds that the strength of the conference is its approach to addressing products from a systemic perspective, where sessions dedicated to products and strategies for their longer life and better design were complemented with policy approaches, consumer interface and engagement strategies, business model innovations and technology advancements, such as Digital Product Passport. One of the highlight sessions was Multi-level Policies for Longer Lifetimes chaired by Jessika Richter and Carl Dalhammer, where for example Michela Puglia from Dyson School of Design Engineering presented Circular Economy Policy Canvas, an interesting mapping on EU policies from the fashion industry perspective. This is very timely research as the EU legislation will have a huge impact on both the products and product systems in the coming years.

Limitations of durability

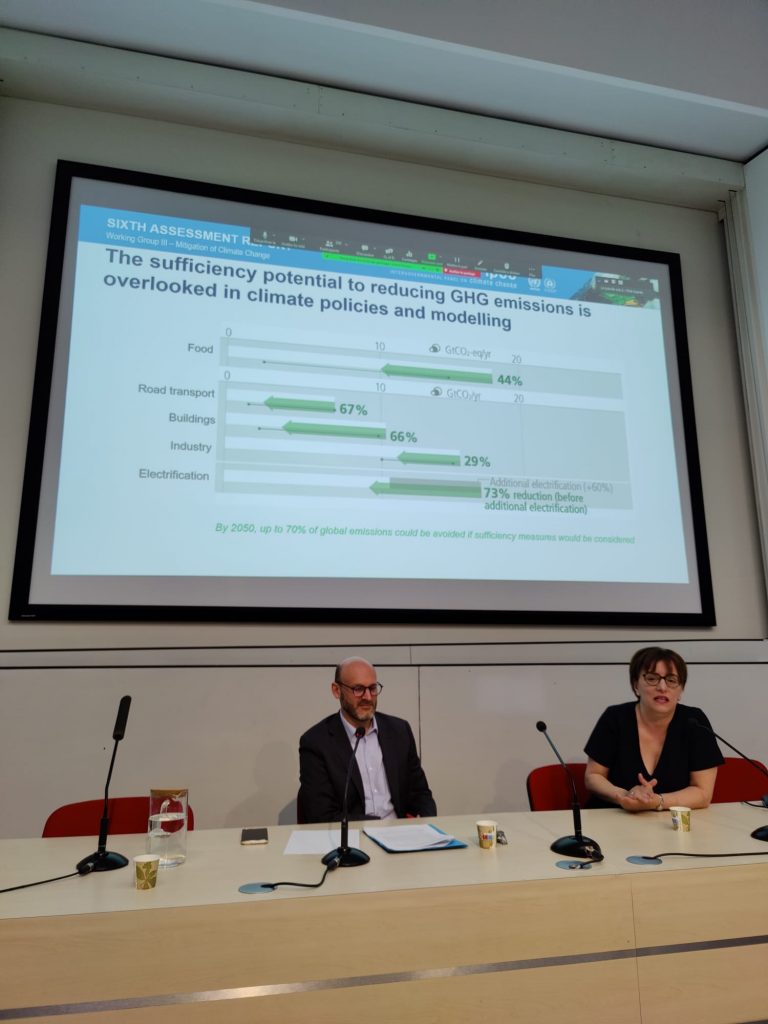

Irene focused on ongoing work in CHANGE around the limitations of durability and noticed that the conference’s view of consumption as replacement-based is still the norm. Only one of the papers she attended, focused on accumulation, namely the paper “Cutting the life of reusable products short: Understanding overconsumption behavior for refill at home FMCGs”, Presented by Catriola Tassell and Marco Aurisicchio, Imperial College London.

Irene reflects: “The most usual way to refer to the difference between how we expect circular strategies to work, and how they actually work, is to use the concept of rebounds, there were several papers on rebounds, and I am looking forward to reading them all.” In the study “Backfire risk in decarbonization potential of 10 circular economy strategies: A meta-analysis of LCA studies on Product Service Systems”, Ryu Koide (University of Tokyo) and colleagues found that 64 % LCAs assume that any “circular offering” displaces “linear products” in a one-to-one basis without even discussing it, a further 17 % assume a displacement rate without empirical basis, 6 % use secondary data to estimate displacement rates in LCAs and only 13 % of all LCAs for all products, all kinds of offerings, conduct research to estimate an empirically based displacement rate. In short, we really don’t know if new ways of producing and consuming offer any improvements.

Returns

In terms of methods and approach to research, we were all impressed about Rotem Roichman’s work on fashion returns, also presented in Tamar Makov’s keynote speech on product returns. Their findings also reinforce a few points important in ongoing SIFO research both in CHANGE and Wasted Textiles, Irene argued: 1) that there is a big difference between demand and production volumes, the second being much bigger, with overproduction driving overconsumption, 2) that no matter how complicated retail, distribution and storage are, production has a far more significant impact, and therefore production volumes deserve much more attention than they get in the field. The paper is “The hidden environmental costs of consumer product returns”, by Tamar Makov, Guilford Glazer Faculty of Business and Management.

Lisbeth Løvbak Berg, from our Clothing Research team, agrees: “It gives further ammunition to our arguments concerning the need for reducing production volumes”. This work was also impressive because trying to map returns is difficult, and because the researchers here used other sources and methods that gave a better picture of the situation. When asked by the audience how the situation with volumes could be improved, Tamar Makov had no suggestions but pointed out that this was not the researchers’ task.

Clothing was a subject of many of the conference papers, and a lot of it was very interesting. Ingun Grimstad Klepp particularly appreciated Ana Neto’s paper, where theories of love are utilised to understand the relations between clothing and people. This perspective shows how important the use phase, and especially a long use phase, is for the development of emotional relationships with clothes. The clothing researchers also participated in a Sustainable Fashion Consumption Network meeting. The network is led by Katja Dayan Vladimirova with the aim of the network of bringing together academic researchers and practitioners working on the issues of fashion consumption in the context of sustainability.

Gender and methods discussion among the PhD students

The PLATE2023 conference included a pre-event for doctoral students working with product lifetimes to discuss commonalities in methods and topics. About 30 doctoral students, including Anna Schytte Sigaard, joined the event which was led by Mikko Jalas who is a professor at the Department for Design at Aalto University. Many of the PhD students working with clothing were using methods similar to wardrobe studies, while also expressing that they were struggling to define their method concretely. They were very happy to hear about the wardrobe studies method and felt that it made sense for them to include a similar framework in their own PhD work. Anna found it very useful to meet and talk to so many doctoral students prior to the conference, especially those with similar academic interests and working on similar topics to mine.

Vilde Haugrønning also enjoyed the discussions and presentations around the topic of gender. Research on fashion and clothing consumption has mostly involved women, which has resulted in much knowledge about women’s clothing consumption patterns but less so about men and the differences between men and women. It is therefore very timely with the study from Stephan Wallaschkowski, who presented on “Gender roles as barriers to sustainable fashion lifetimes: How a deconstruction of norms can extend the use phase of garments”. His research will be an important reference for the CHANGE project and Vilde’s PhD, which aims to look at how social constructs of gender have an influence on the material flow and volume of clothing in wardrobes.

We all returned home with more knowledge and contacts, and will probably also prioritize PLATE in years to come.