The Wasted Textiles team have had many meetings with policy-makers, politicians, NGOs, textile industry representatives and other interested parties regarding our Targeted Producer Responsibility proposal. We have collected questions we have been asked and here you will find the answers to these questions. If you have other questions, feel free to send them to us, and we will answer them as best we can, and make them publicly available.

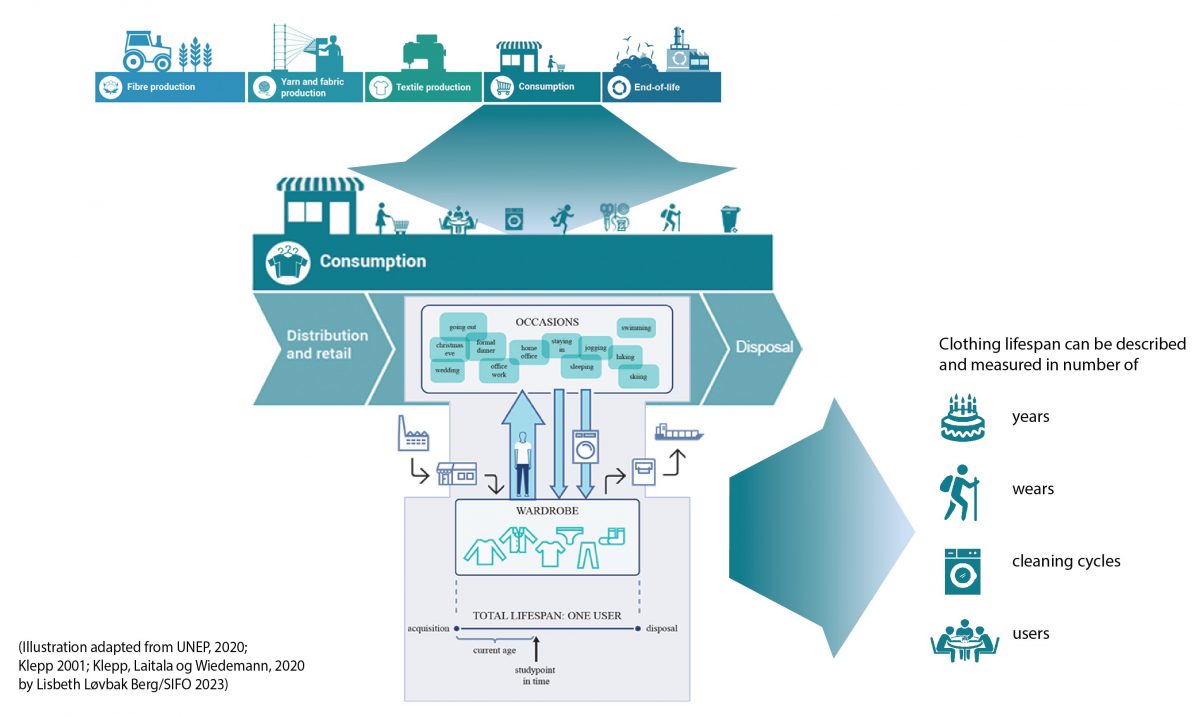

Q: How to obtain knowledge about the lifespan of textiles?

A: Lifetime can be measured in number of years, or the number of times something is used. The proposal is to use the length of the use phase as the most important criterion. We propose that the brand and date of production/import will be made mandatory in the future legislation. In the long term, it will then be possible to measure how long the usage phase is on average per brand. We will also be able to say something about the number of uses. The clothes that have not been used will usually be recognizable, and likewise, clothes that have been used until they are worn out. The main method of TPR will be waste analyses and it is possible to do the analyses of the life span in different ways, also related to the type of textile.

Q: Is it only the quantity and age of the textiles in the waste stream that determine the size of the fee?

A: Our proposal is that the quantity and age of discarded textiles shall determine the fee together with the cost of capturing the End of Life (EoL) value for the products. This means that textiles with a high price on the second-hand market, or based on their material composition are a resource for recycling, will have a lower price or even not generate a fee at all, in accordance with the “polluter pays” principle.

Q: How to guarantee that the product carries information about the garment and the brand?

A: The rules today safeguard this to a certain extent, as the labels or the printed information need to withstand a certain number of laundry cycles. It is often also possible to determine the brand by visible logos or because the clothes are recognizable for other reasons. In practice, some will be unidentifiable, but as the sample pick analysis will give representative numbers, this is not the biggest hurdle. There will be enough waste to make statistical and significant compilations.

Q: With the Digital Product Passport (DPP) work underway to update the rules on what information is mandatory on textiles, is it premature to require that the date of manufacture (or date of placing on the market) must already appear on the label?

A: No. There can be interim solutions on the way to a product passport, and as picking analysis is a known method to gather data from waste streams, this is vital in order to quickly assess how long products have been in use before they are discarded. It is possible to analyse the age of clothes in the waste streams without dating the clothes, but dating will give better accuracy and make the analyses easier. In addition, the dating of clothes will have a number of positive effects for consumers, such as giving consumers a greater opportunity to compare the technical quality of the clothes and determine how long they have been in use. This will strengthen the right to complain which is linked directly to the number of years, thus empowering EU citizens. It will also be an important link to transparency about production conditions. We, therefore, suggest that product date labelling should be included in the coming revision of the EU Textile Labelling Regulation, independently of EPR/TPR.

Q: Who will do the waste picking analysis?

A: We envision the work being carried out by third-party analysis agencies/research institutions with expertise in picking analyses and apparel, overseen by a public authority to oversee the implementation and ensure transparency.

In the Wasted Textiles project, the analyses are based on a collaboration between an analysis agency, MEPEX, with experience from sorting agents for other waste streams, researchers with experience with textiles, and the largest charity in Norway, along with Consumption Research Norway (SIFO)’s experience with different versions of wardrobe methods. Collectively, a method has been developed to look at the composition of the textile waste. Based on this work, it will be possible to further develop a method that meets the specific requirements of an EPR/TPR system.

Q: How to estimate how old a garment is by looking at waste streams or reuse collection streams?

A: Unused clothes are generally recognized by the fact that they have price tags on them, or that they are found in large quantities of similar clothes (unsold). Age can otherwise be assessed based on style, technical details and wear-and-tear. We are not talking about detailed information, but about broad assessments. Textile waste today consists of textiles produced over many decades and there have been technological and aesthetic changes in apparel over the past 50 years, although apparel has not changed as quickly as e.g., electronics. Accuracy will of course be easier when the date becomes a mandatory part of labelling textiles. Accuracy will also be better if the staff who carry out the analysis have the appropriate textile expertise.

Q: What are the criteria for a TPR fee?

A: TPR can be used and combined with different varieties of EPR and other political instruments. If it is to have the effect of reducing overproduction and making fast fashion out of fashion, then it depends on the fee being high enough to affect the producers, their business models and downstream decisions. However, it is not the size of the fee that distinguishes TPR from other EPR systems, but the way it is calculated.

Producers would pay different levels of EPR fees depending on:

- How old the clothing is when going out of use (very old clothing generates no fee, while very new would generate a high fee)

- How reusable/recyclable the clothing is (clothing types with profitable pathways have a low fee)

TPR will ensure a level playing field for a European-based textile industry, global brands and online producers, so-called ultra-fast-fashion brands. TPR will catch all textile waste, regardless of where the garment was made or imported from, thus addressing the challenge of online trade/e-commerce and “free-riders”. Further work is needed on the details of how the fees are calculated for each individual producer, for specific product groups or for the industry as a whole.

Q: Can picking analysis actually underpin the legal validity of fees?

A: The legal foundation, implications and further development of TPR are in the current EU Waste Framework Directive, and in the coming revisions. The current WFD (article 8a) defines minimum requirements for member states and their EPR-systems, f. ex. stating that eco-modulation shall be used when it is possible. But until now we have not seen eco-modulation being used in accordance with the waste hierarchy, nor the polluter pays-principle, when it comes to irresponsible production and consumption, and its waste export, and there are limitations in the current directive when it comes to setting fees that go beyond the waste phase. The EU textile strategy from March 2022 announced that there will be a harmonised producer responsibility in the EU set forth in the coming revisions.

We will rely on legal experts and funding for further work with the legal aspects of TPR. It is likely that the retroactive aspect will be contended. If producers are held responsible for the waste they have produced long before the scheme comes into effect, they will balk. It will, however, only be a temporary problem. It is also possible to use TPR combined with sales/import statistics, so that TPR is used to modulate the fee, but that it is based on the imports/production taking place at the same time. We consider it unlikely that the analysis of the waste itself would not be reliable enough. Picking analyses are used on other waste streams and is a recognized method.

Q: Will TPR be costly to operate?

A: The costs of operating the scheme will be covered by the fee, as is normal for other control schemes for industries. TPR is based on national samples taken annually or every two years, and is assumed to be administered at low cost.

For TPR to work (reduce quantities and thus environmental burdens) it is important that the fees are high enough. This will provide money that can be used for, among other things, the operation of the system. In existing EPR-schemes the fees are often set very low so that there is little room for covering other than minimum administrative costs.

In general, there is too little waste regulation supervision and with many new EU regulations to be followed up, it is necessary to strengthen supervision on national and municipal levels. The knowledge that the picking analysis will provide is important data for monitoring the effect of the EU’s textile strategy and for making the best possible use of textile waste. It is difficult to imagine effective policy and product development without knowledge of the waste.

Q: How can we trust those who will be doing the picking analysis, that the data they collect is good enough to eco-modulate fees based on the findings?

A: In contrast to much environmental work, TPR is not based on information provided by the actors themselves, but by an independent third party with no financial interests in the matter. Why should a research or analysis agency not be trusted? It is, after all, common to use a third party to obtain information precisely to ensure independence. A major problem in the textile industry is that concepts, perspectives and what is perceived as knowledge are often produced by the industry itself and its organisations. Selective analyses, on the other hand, can be carried out by independent analysis agencies/researchers.

Q: Will TPR affect companies that want to invest in circular business models and charities that are dependent on revenues from second-hand trade?

A: Circular BMs, such as repair, rental, etc. are struggling financially today due to the competition with cheap new clothes. By making it more expensive to sell what hardly gets used, the over-production will be impacted and eventually reduced (provided the fee is high enough). This will strengthen the possibility for such BMs. The companies that work with further processing of textile waste (repair, redesign, recycling and all intermediate forms) will be able to receive financial help for product development and support from the EPR system and this subsidy will improve their financial sustainability.

Q: In the EU, 99,9% of the actors in the textile sector are SMEs. How will TPR capture meaningful data about them, and ensure that they are not treated unfairly?

A: For once, we are lucky that the fashion and sports apparel sector are dominated by big, global companies with large volumes. This means that they will dominate in the picking analysis.

Q: How will the collected fees be allocated and used?

A: The allocation of the fee has not been elaborated in the proposal for a TPR system. However, we believe that it is important that the TPR funds will be allocated to support as a minimum (non-exhaustive list):

- operation of the system (incl. picking analysis and calculations, the logistics)

- support proper use of collected textiles according to the waste hierarchy, incl. charities, markets for reuse and repair

- support the work with reducing synthetic textiles, preventing the spread of microplastics and cleaning up the textile waste in developing countries

- support municipalities that need to build up collection, sorting and treatment facilities

- support countries, regions, businesses and NGOs in the global south in cleaning clean up landfills and rivers and establish functioning waste management systems

- stimulate technology innovation, research, development and investments

Q: Can TPR be useful for other policy measures than EPR?

A: TPR is a way of “capturing” the use phase, which otherwise remains a “black hole” in LCAs. In other words, a very important factor for calculating environmental impact in the whole lifecycle of a product, is not taken into account. TPR will make a valuable contribution to gathering meaningful data – and thus can have an impact on many policy measures, especially the ones based on LCA data.

Q: The EU Textile strategy aims for durable, repairable, recyclable apparel and footwear, that also contains recycled content – does TPR contribute to this, or is it counter to these aims?

A: TPR will contribute by bringing forward knowledge and data on how effective these aims are in delivering on the issues around durability. Through the picking analysis it is possible to collect various information on discarded or donated products, i.e., if the discarded or donated items have been repaired, or other relevant information related to the Textile Strategy aims.

Q: Does the TPR have the potential to address just transition, more local value-chains, eco-design and other issues that the EU are addressing through other strategies and programs?

A: The results from the picking analysis will feed into eco-modulation, and be the opposite of traditional eco-design, which only projects assumptions on lifespan. The data collected will be ‘proof of the pudding’ on what actually has a long lifespan, and cancel part of the eco-design directive, through providing actual data and incentives for making lasting products. TPR will use the market forces, and let the companies themselves decide how they tackle this, but make it costly to make products nobody wants. This will be valuable for the New European Bauhaus. We also see synergies for Farm to Fork, the EU’s new Soil Mission, and other programs and strategies, for example, the Plastic strategy. We know the EU aims for a more holistic, non-siloed way forward, and TPR offers an opportunity for this, based on how to award apparel that stays in use for a long time (indigenous, traditional, local, etc.) up against low-quality products that have a very short lifespan.

Q: How will TPR help to phase out fast fashion?

A: If the fees are high enough to deter the increased plastification of our wardrobes and for clothing that we keep, use and love for a long time, to be awarded amnesty, then TPR will help phase out fast fashion.

Q: How will this affect the developing countries, who rely on second-hand clothes from the EU and the trade of these clothes?

A: TPR has the potential to affect developing countries in two ways. Firstly, the TPR fee should address the issue of waste colonialism, i.e., quantities of textile waste exported (as mentioned earlier in the paper but needs further study for concrete proposals).

Secondly, in line with the EU’s strategic goal to handle its own textile waste rather than exporting it to the Global South, TRP will indirectly affect this export in the long run, through the expected reduction of fast fashion and the volumes being exported.

TPR is also an opportunity for EPR to reduce quantities imported into the EU and thus if the fee is set high enough, it will affect the quantities that go out of use and thus what is exported to developing countries. This is very important, as it is the Global North that creates the major waste problems, which has been recently documented by EEA, Changing Markets Foundation and The OR Foundation. TPR’s goal is to affect the quantities being produced (fast fashion) and exported as waste and thus reduce negative environmental impacts and the related problems in production, use and disposal. These are environmental problems that particularly affect developing countries in that both the production takes place there and that the waste ends up there.

Q: Can TPR be used in other product areas?

A: Yes. That is a good idea to explore. As far as we know, there are no similar systems for other product groups; however, many products are sold with dates and also information on expected lifespan, which is a good basis for developing a TPR system. It would be possible to install a counter in f. ex. a laundry machine or coffee maker, so that the fee is not only based on years of use, but also laundry cycles or coffee-pots made. Using both years of service life and other available information in the modulation of the fee will contribute to more durable products for many product categories.

See the full briefing paper that was sent to the EU representatives below.